The Politics of the Dead: Living heritage, bones and commemoration in Zimbabwe

Author: Joost Fontein, Social Anthropology & Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh

Date: 10/08/2009

html / PDF

ISSN 2073-4158

Biography

Lecturer in social anthropology at the University of Edinburgh, editor of the Journal of Southern African Studies, and co-founder and editor of a new online publication called Critical African Studies. His first monograph, entitled The Silence of Great Zimbabwe: Contested Landscapes and the Power of Heritage (UCL Press), was published in 2006 and he is currently writing a book entitled Water & Graves: Belonging, Sovereignty, and the Political Materiality of Landscape around Lake Mutirikwi in Southern Zimbabwe..

Contents

The burial of Gift Tandare

Heritage and commemoration

Heritage and commemoration in Zimbabwe

Liberation heritage

Unsettling Bones

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to explore the ambivalent agency of bones as both ‘persons’ and ‘objects’ in the politics of heritage and commemoration in Zimbabwe. It discusses a recent ‘commemorative’ project which has focused on the identification, reburial, ritual cleansing and memorialisation of the human remains of the liberation war dead, within Zimbabwe and across its borders (Mozambique, Zambia, Botswana, Angola and Tanzania). Although clearly related to ZANU PF’s rhetoric of ‘patriotic history’ (Ranger 2004b) that has emerged in the context of Zimbabwe’s continuing political crisis, this recent ‘liberation heritage’ project also sits awkwardly in the middle of the tension between these two related but somehow distinct nationalist projects of the past (heritage and commemoration). Exploring the tensions that both commemorative and heritage processes can provoke between the ‘objectifying’ effects of professional practices, the reworkings of contested ‘national’ histories, and the often angry demands of marginalised communities, kin and the dead themselves (for the restoration of sacred sites or for the return of human remains), the conclusion that this paper works towards is that the politics of dead is not exhausted by essentially contested accounts or representations of past fatal events, but must also recognise the emotive materiality and affective presence of human bones in themselves. Engaging with recent anthropological discussions about materiality and the agency of objects, it is suggested that in the ambivalent agency of bones, both as extensions of the consciousness of the dead, as spirit ‘subjects’ or persons which make demands on the living, but also as unconscious ‘objects’ or ‘things’ that retort to, and provoke responses from the living, the tensions and contradictions of commemoration, heritage and the politics of the dead are revealed.

The burial of Gift Tandare

In early March of 2007, whilst the attention of the international media was focusing on the brutal beating by police of the leader of Zimbabwe’s opposition MDC (Movement for Democratic Change) party, Morgan Tsvangirai, the dramatic events that surrounded the funeral of Gift Tandare – a little known MDC activist who was shot by police on the same day - was being reported in the local independent media. The events unfolded as follows1. Soon after the fatal shooting during a peaceful prayer rally in the Highfield suburb of Harare on Sunday, 10th March, mourners began to congregate in large numbers at the deceased’s residence in the high-density suburb of Glen View (MDC News Brief, 19/3/07). Apparently fearing any further disturbances or protests, armed police and soldiers were sent in to disperse the mourners, resulting in more injuries and people being shot.

Then, a few days later, it emerged that Chief Kandeya, the ‘traditional authority’ in charge of Mashanga village in Mt Darwin where the Tandare family’s Kumusha (rural home) lies, and where his family had sought to bury him, was refusing to allow the funeral to take place on the grounds that Gift Tandare was an MDC activist and ‘burial in his area is reserved for ZANU PF [Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front] supporters only’ (MDC News Brief, 19/3/07). Later, when the chief demanded payment of four cows for the burial to go ahead, Tandare’s family, being unwilling or unable to pay this, decided Gift would instead be buried in Harare at Granville cemetery (SW Radio Africa, 17/3/07). This decision, as Gift’s elder brother was quoted as saying, ‘has been welcomed with joy as everyone wanted to attend his burial’ (ibid.). But this was not to be. On the Saturday night (18/3/07) before the funeral, a heavily armed police convoy turned up at the Tandare house to take only close relatives for a hastily prepared private burial. While mourners fled, the family were told that ‘the chief had been talked to’ (MDC News Brief, 19/3/07), and that the police wanted Gift’s wife to sign another burial order granting them permission to bury Gift as originally planned in Mt Darwin.

The following morning reports from the funeral parlour explained that ‘men in suits’ (i.e. Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) agents) had come in the early hours and ‘forcibly removed the body…for burial’, coercing ‘Gift’s sister in the presence of her fearful uncle to sign the burial order’ (MDC News Brief, 19/3/07). While this was going on, Gift’s wife had gone to get a court order against the police barring them from interfering with the funeral arrangements, an order that was granted but also promptly ignored by officials (Cape Argus (SA), 19/3/07), who proceeded to bury the body in ‘the absence of his wife and children’ in a ‘mafia style ceremony’ (MDC News Brief, 19/3/07). According to The Standard (18/3/07), orders to remove the body and carry out the burial, ‘as quickly as possible’, had come from the President’s office, because authorities were worried that ‘the activist’s burial could be turned into a platform for an anti-Mugabe tirade by opposition supporters, already angered after the brutal attack on MDC President Morgan Tsvangirai’.

These recent events illustrate how intense the politics of the dead, and what to do with their remains, can be in the context of Zimbabwe’s ongoing political turmoil. It is well documented that the funerals of people killed in political violence can often become sites of protest and further violence (cf. Allen 2006; Feldman 1991 & 2003), hence it is no surprise that the ZANU PF government and the police were concerned to avoid a high profile, public funeral in Harare2. But the controversies surrounding the burial of Gift Tandare also point to a deeper complexity of meanings and contests that can be involved in ‘the politics of the dead’ (cf Odhiambo & Cohen 1992; Verdery 1999). Efforts to ‘dignify death’ can often provoke a complex politics of burial, which, in the case of colonial Bulawayo discussed by Ranger, revealed ‘the existence of multiple and contesting agencies’ that crosscut existing tensions not just between ‘colonial’ and ‘African’ efforts to control city space, or between ‘traditional African’ and ‘modern Christian’, or ‘rural’ and ‘urban’ mortuary practices, but also between the dictates of rival churches (whether African independent or missionary), burial societies and the entangled demands of class, wealth, labour, kin and gender loyalties, or even those of divergent imaginaries of cultural and ethnic nationalism (Ranger 2004a: 110-144).

Chief Kandeya’s initial refusal, and later hefty financial charge, for permission to bury Gift in Mashanga village is perhaps less remarkable for the ‘political’ motivations that apparently lay behind it, and more so for the simple fact that chiefs have the authority to decide who gets buried within their territories. This relates both to a past colonial ordering of land and authority in which commercial/European and communal/African areas of land were administered under separate regimes of rule (cf. Alexander 2006; Mamdani 1996), but also to a new streak of ‘traditionalism’ that has emerged in Zimbabwe recently, which has seen the functions and powers of chiefs and traditional leaders revived and expanded out of communal areas into resettlement schemes, farms, rural district councils and land committees (Fontein 2006b & 2007; Mubvumba 2005); a trend that has been mirrored by developments across the southern African region (Buur & Kyed 2006; Kyed & Buur 2006; Maloka 1996). The different burial orders that were being handled and signed, and the subsequent court order, granted but ignored, barring police interference in the funeral arrangements, all indicate how complex struggles over sovereignty and regimes of rule can emerge in disputes over how to handle the remains of the dead. Although often manipulated by chiefs and ruling clans for their own local (and indeed financial) interests, the jurisdiction of so-called ‘traditional authorities’ in rural areas across Zimbabwe, over the burial of the dead in the landscape, relates closely, in cultural terms, to their function as living guardians of the soil, as descendants of the ancestral, often autochthonous, owners of the land, who must be appeased to ensure rain, soil fertility and prosperity (Lan 1985; Bourdillon 1987). Hence, it is no surprise that both the existence of past graves, and the burial of the recently dead, have become central to the complex restructuring of authority over land in Zimbabwe that has emerged since the adoption of Fast Track land reform in 2000 (cf. Marongwe 2003; Chaumba et al. 2003a & 2003b; Mubvumba 2005)3.

Reports about the controversy over the burial of Gift Tandare also suggested the existence of tensions among Gift’s close relatives and kin, as indeed can often emerge at funerals in Zimbabwe, particularly between paternal and affinal relatives over funeral arrangements, the inheritance of property, and responsibility for the care of dependents. Some reports stated that it was Gift’s paternal sister and uncle who left with the police and later signed, under duress, the burial order that ‘allowed’ the secret ‘mafia style’ burial, while his wife and her mother, both affines, hid. And it was the wife who later applied for and was granted the ineffectual court order (MDC News Brief, 19/3/07). Without drawing too much out of scant information, these references do suggest the presence of a subtle subtext of family tensions intermeshing with the political manoeuvres of the ruling and opposition parties. At the very least, belief in the dangerous liminality of the deceased’s spirit during the immediate period after death and before burial, which anthropologists have noted is common among Shona peoples (Bourdillon 1987:119-208; Ranger 1987:174; Lan 1985) particularly after violent and traumatic death, must have made the political circumstances surrounding the funeral arrangements even more troubling for Gift’s family.

While the authorities may have been concerned about the potential threat to public order that a high profile funeral in Harare’s volatile suburbs could provoke, the ‘secret’ burial of Gift may also have functioned as a means of circumventing the creation of a memorial landscape to work against ZANU PF’s own highly politicised commemorative project, as exemplified by it’s monopoly of the North Korean built National Heroes Acre in Harare. The MDC, for their part, firmly inscribed Gift Tandare on their counter–register of ‘National heroes’ amongst all the other ‘innocent Zimbabweans who have been murdered for merely asking for a better life in a free and democratic Zimbabwe’ (MDC News Brief, 19/3/07). While ‘state’ interference in the death and burial of Gift Tandare and others (see also SW Radio Africa, ‘Abducted Zimbabwean journalist found dead’, 6/4/07) seems to highlight the current insecurity of the ruling regime in Harare, a longer view of commemoration in Zimbabwe since independence in 1980 (Kriger 1995; Werbner 1998, Brickhill 1995, Alexander et al.2000) indicates that attempts to manipulate the representation of the recent past, and memories of violence, has been part of the ruling party’s strategic historical project since independence, far predating its recent turn to a new nationalist and very exclusionary, political rhetoric that Ranger (2004b) has called ‘patriotic history’. As Werbner (1998) and Kriger (1995) have described, the controversies engendered by the efforts of the 1980s and 1990s to appropriate the dead for political purposes often provoked tensions not only between the ruling party and any opposition parties (then ZAPU, now the MDC), but also between political elites and commoners, the ‘chefs’ and the ‘povo’, and between state and kin, and even within the fractious ruling party itself. The thwarted attempts in Matabeleland, described by Alexander et al. (2000:259-264), to commemorate both the unacknowledged dead of ZIPRA’s military campaigns during the liberation struggle, and the victims of the Matabeleland massacres of the gukurahundi period in the 1980s (see CCJP 2007) illustrate the extent of the ruling party’s ‘heavy-handed obstruction’ (Alexander et al. 2000:264) of alternative forms of commemoration in the 1980s and 1990s.

The purpose of this paper is to consider this history of the politics of memory and commemoration in Zimbabwe in relation to both a more recent ‘commemorative’ project which has focused on the identification, reburial, ritual cleansing and memorialisation of the human remains of the liberation war dead within Zimbabwe and across its borders (Mozambique, Zambia, Botswana, Angola and Tanzania), and that other ‘nationalist’ project of the historical imagination that has centred on ‘heritage’ (see Fontein 2006a). Indeed the recent project of reburials in Zimbabwe and across its borders, although clearly related to the rhetoric of ‘patriotic history’ (Ranger 2004b), seems to sit awkwardly in the middle of the tension between these two related but somehow distinct nationalist projects of the past. It is, after all, National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ), the parastatal responsible for cultural heritage, which has been primarily charged with carrying out the exhumations and reburials involved in this larger, UNESCO sponsored, SADC (Southern Africa Development Community) wide project focusing on so-called ‘Freedom War heritage’4. I will suggest that for them, involvement in this project is not merely playing lip service to the political demands of the ruling party’s rhetoric of ‘patriotic history’, or the opportunities for research funding that this has offered, but also relates to recent developments in concepts of and approaches to ‘intangible heritage’ which have increasingly emphasised its living, ritual, and spiritual aspects.

Like the contested burial of Gift Tandare, the exhumations and reburials of liberation war dead engage with sometimes competing, more often intermeshing, attachments to the dead; by close kin, clans, ethnic and regional communities or work and war comrades, and political affiliates, as well as political parties and the ‘state’. Exploring the tensions that both commemorative and heritage processes can provoke between the ‘objectifying’ effects of professional practices (e.g. archaeology, forensic science and heritage management), the reworkings of contested ‘national’ histories, and the often angry demands of marginalised communities, kin and the dead themselves (for the restoration of sacred sites or for the return of human remains), the conclusion that this paper works towards is that the politics of the dead is not exhausted by essentially contested accounts or representations of past fatal events, but must also recognise the emotive materiality or affective presence of human bones and remains in themselves. This perspective builds on Verdery’s important discussion of the complex ways in which bodies can animate politics, but moves beyond it by suggesting that the political efficacy of human remains is not limited to their ‘symbolic effectiveness’ (1999: 27-29). As Fontein & Harries have recently pointed out:

in Verdery’s work on bodies, the ‘thereness’, the material presence, is critical only to the symbolic efficacy of human remains - in the way they make the past present. But this ignores the stuff of corpses in themselves – material presence merely reinforces layers of cultural meanings.

(Fontein & Harries 2009:5).

With a view to further exploring how the materiality of bones relates to the way they can animate politics, I will finish by suggesting that it is in the ambivalent agency of bones, both as extensions of the consciousness of the dead, as spirit ‘subjects’ or persons which make demands on the living, but also as unconscious ‘objects’ or ‘things’ that retort to, and provoke responses from the living, that the tensions and contradictions of commemoration, heritage and the politics of the dead in Zimbabwe are revealed.

Heritage and commemoration

In many ways heritage and commemoration are very similar. Both involve processes of selective remembering and forgetting – or representing and silencing – the past, which are fundamentally political, contestable and often very controversial. Both have been central to nationalist projects and both have often involved the marginalisation not only of different representations of the past, but also of other ways of remembering, managing or dealing with it and its physical remains. Both reify particular ways of remembering or recounting the past, but also of dealing with its material remains, in the form of objects, landscapes and bones.

But apart from the similarities, there are also important differences or divergences. In very general terms, if heritage represents an inheritance from the past, then commemoration involves a response to the demands of the dead. Commemoration often relates to more recent, and sometimes very traumatic, events, involving the death and sacrifice (Rowlands 1999) of an individual or a group for, or on behalf of, a ‘nation’ or another large ‘identity group’, while ‘heritage’ – at least in its more old-fashioned, ‘monumentalist’ manifestations – may appeal to achievements, constructions or practices in the ‘deeper’ past for the purposes of the (often nationalist) present. Indeed this focus on different time periods in the past is or was often enshrined in law. For example, in Zimbabwe, as Ndoro and Pwiti (2001:24) have pointed out, now out of date national monument legislation prescribed that for a site to be declared a national monument, and therefore afforded legal protection, it must have existed before 1890. This, therefore, excluded recent liberation war sites5.

Both ‘heritage’ and ‘commemoration’ inevitably involve selective forgetting (Forty & Kuchler 1999) or silencing in order to legitimise a cause in the present through references to the past, but while commemoration often urges the living not to forget a debt to the dead (even as war memorials may seek to foster a simultaneous forgetting of the grim actualities of death - Rowlands 1999:137), heritage more often seeks to narrate and represent the practices and achievements of the past in order to inform or entertain the living. In more material terms, while state commemoration often involves the massive construction of monuments to encourage or cajole the living into particular forms of remembrance, heritage processes commonly involve selectively preserving, conserving, representing and managing existent remains of the past, for the purpose of informing, educating and entertaining the present. Commemorative sites and events are often more serious affairs, akin to a funeral, with an emphasis on the loss and sacrifice of the dead, the ongoing debt of the living and their requirement to ‘feed’ (Rowlands 1999:144) or ‘finish the work of the dead’ (Kuchler 1999:55), whilst heritage sites can be more frivolous, less emotive of sacrifice and loss, and much more amenable to commodification. If heritage is a celebration of – or declaration of faith in – the past (Lowenthal 1998:121) that seeks to inform the present, selectively, about it, commemoration often carries not only demands for an atonement or acknowledgement of the debt of the living to the sacrifices of the dead, but also functions of reconciliation, healing and the resolution of suffering, even if it is not always ‘obvious how they do this’ (Rowlands 1999:142)6.

Of course, these distinctions between heritage and commemoration can be very murky indeed. This is perhaps best exemplified by the examples of Auschwitz Concentration Camp in Poland, Robben Island in South Africa, and the Old Bridge of Mostar in Bosnia, all of which are world heritage sites (see http://whc.unesco.org/en/list). Heritage can take on the commemorative functions of post conflict reconciliation, although at times, as in the case of the first two just mentioned, they almost appear as ‘anti-heritage’, in the sense that such monuments demonstrate not an historical precedence for the present, as a symbol of past achievement, but stand rather as examples of something not to be repeated. Such ‘anti-heritage’ can be deftly reconfigured in different ways, as, in the example of Auschwitz, a ‘symbol of humanity's cruelty to its fellow human beings in the twentieth century’ (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/31) or at Robben Island, to ‘symbolize the triumph of the human spirit, of freedom, and of democracy over oppression’ (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/916).

While these examples illustrate how foggy the distinction between heritage and commemoration can be, it should be remembered that these are only three out of 830 world heritage sites. The definitions of heritage espoused by UNESCO’s ‘world heritage system’ (cf. Fontein 2000) do seem largely to exclude the commemorative sites and processes which form that other, highly conspicuous, backbone of national imaginative investments in the past everywhere, alongside heritage, indicating that an exploration of convergences and divergences of heritage and commemorative processes is worth pursuing. One possible line of enquiry may be to explore of how the passage of time facilitates the transformation of sites of memory and commemoration into places of heritage. If, as Rowlands has suggested, ‘memorials become monuments as a result of the successful completion of the mourning process’ (1999:131), then maybe, by extension, it is as objects of commemoration fade into a deeper past, that space is opened up for technologies of heritage to activate. Paola Filippucci’s work on landscapes and memory on the Western Front in Argonne, France, does suggest that it is the fading of immediate memory with time that has provoked increased interest in experiencing, through re-enactments and by sensual exposure to the battle-scared landscapes, what life in the trenches might have been like (Filippucci 2004: 44-45). So World War One landscapes, which have for long been dominated by the monumentalism of state commemoration, become increasingly suffused with heritage paraphernalia, such as re-enactments, trench tours and tourist centres.

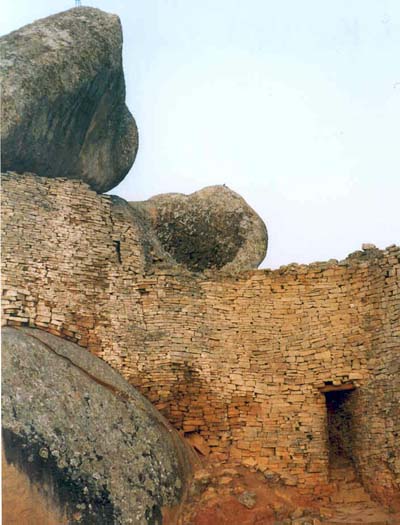

Perhaps we could suggest a similar temporal dimension to commemorative and heritage processes in Zimbabwe. If the 1980s and 1990s were marked by growing emphasis upon ‘healing the wounds’ of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle, as reflected in a proliferation of literature onspiritual healing and the resolution of suffering by churches, ‘traditional’ n’anga healers, sangoma possession cults and the Mwari cult of the Matopos Hills (Ranger 1992; Reynolds 1990; Schmidt 1997; Werbner 1991), then perhaps it was the resolution offered by these processes which provided the enabling conditions for the emergence of NMMZ’s and indeed SADC’s Freedom Heritage Project in 2004. But, of course, this does not quite work. Not only is it far from clear that the scars of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle have been satisfactorily healed or resolved (and in fact much evidence points to the opposite), far more disturbing are the terrible legacies of the gukurahundi massacres in Matabeleland during the 1980s, which continue to haunt Zimbabwe’s troubled postcolonial milieu. While the bones of unidentified dead from both these violent periods of Zimbabwe’s recent past continue to resurface from the earth of unmarked shallow graves and mass burial sites across the country7 – most recently when villagers in Mt Darwin ‘began discovering skeletons as we tilled our lands’ after heavy rains (‘Mt Darwin’s killing fields’ Sunday Mail 13/1/2008) – relatives of deceased gukurahundi victims in Bulawayo and Matabeleland have continued to demand ‘to know where our loved ones are buried’ (Letter from Z. Omphile, Bulawayo, Daily News 3/9/01). NMMZ’s liberation heritage project – at least the reburials that have been involved – must in part be understood as a response to the still unresolved legacies of both pre and post independence violence, even as it fits both with UNESCO’s turn towards intangible, ritual and spiritual heritage, and ZANU PF’s revitalized but narrowed nationalist historiography. If the murkiness of distinctions between heritage and commemoration defies the usefulness of making definitions or assertions in such general terms, it may be more profitable to think in terms of very specific examples of where commemorative and heritage practices have coincided, overlapped, confronted or excluded each other. In order to do this, I turn briefly to Great Zimbabwe national monument in southern Zimbabwe (see figure one), the country’s most important heritage site from which its name derives, which was the subject of a recently published monograph (Fontein 2006).

The Hill Complex at Great Zimbabwe

Heritage and commemoration in Zimbabwe

In his account of what he calls the ‘heritage crusade’, Lowenthal (1998:94) discusses the difficulty of defining ‘heritage’. Indeed, Lowenthal does not attempt to draw a distinction between commemoration and heritage at all, preferring rather to focus on the disjuncture between ‘heritage’ and ‘history’. As he puts it:

Heritage diverges from history not in being biased but in its attitude toward bias. Neither enterprise is value-free. But while historians aim to reduce bias, heritage sanctions and strengthens it. Bias is a vice that history struggles to exercise; for heritage, bias is a nurturing virtue.

(Lowenthal 1998:122)

In my research into the politics of heritage at Great Zimbabwe (2006a), I have found this distinction between ‘history’ and ‘heritage’ hard to maintain. In relation to what I have called the professionalisation of the representation and management of the past at Great Zimbabwe, one key problematic aspect of heritage processes is precisely their reliance on, and reification of, ‘modern’ academic, ‘objectifying’ approaches to dealing with the past, such as history, and particularly archaeology, but also museum practices of conservation and preservation. Following Kevin Walsh (1992), I argued that archaeology is a distancing, disembedding mechanism, which has appropriated the authority to represent and manage the past from those individuals and groups who have other ways of understanding and relating to it – other perspectives on the past, its relationship to place and landscape, and its demands on the present. At Great Zimbabwe it was the dominance of archaeological narratives of the past that followed the infamous Zimbabwe Controversy of the early twentieth century (Kuklick 1991), and later the gradual professionalisation of the management /conservation of its remains, which has in effect appropriated and alienated the site away from disputing local clans which each have their own attachments to the site, their own historical narratives or history-scapes (Fontein 2006a: 19-45), and their own needs and means of responding to the demands of the past, in the form of tributes and rituals for the ancestral spirits, and the Voice, associated with it.8

Increasing after independence in 1980, the growing professionalism of NMMZ – reinforced by what I called the anti-politics of world heritage (2000; 2006a: 185-212) – meant that local communities were unable to carry out ancestral rituals to ensure rain, fertility, wealth and the welfare of the living. It was not only the competing interests and practices of local clans, which were increasingly marginalised as heritage management was ‘professionalised’. After 1980 Great Zimbabwe became subject to a whole host of attempts by spirit mediums and ‘traditionalists’ from across the country to hold ceremonies and rituals there to thank the ‘national ancestors’, such as Nehanda, Kaguvi and Chaminuka, for the successful liberation of the country from colonial rule, and to appease the spirits of dead guerrillas killed during the war. These high profile ‘national’ rituals to appease the ancestors, settle the spirits of the war dead, and cleanse the perpetrators of violence, were also prevented by NMMZ as they increased their ‘professionalising’ control over Great Zimbabwe during the 1980s and 1990s.

In terms of the tension between commemoration and heritage that I have scantly proposed above, in a sense, this professionalisation of the past meant, at least for those whose rituals and ceremonies were being excluded, that the site was not commemorative enough. Heritage processes objectified and distanced the past to the exclusion of other perspectives which are less concerned with archaeological narratives about the achievements of Great Zimbabwe’s ‘original’ builders between the twelve and fifteenth centuries (the primary concern of NMMZ archaeologists) and more with the need to respond to the ancestral spirits and the Voice that used to dwell there about or were associated with it. If commemorative processes involve rituals, memorials and monuments that are understood as a response by the living to the demands of the dead - however the dead are (re) imagined, however the response is structured, and regardless of whether at the level of the ‘nation’, clan or kin – then any kind of commemoration, or ‘feeding [of] the dead’ (Rowlands 1999:144), at Great Zimbabwe was increasingly frowned upon throughout the twentieth century.

The distancing effects of heritage processes against commemoration at Great Zimbabwe have a long history. Alongside Rhodesian efforts to claim the Zimbabwe sites as their own ‘heritage’ to justify colonial conquest, based on fallacious beliefs about its ancient, non-African origins, there were also early attempts to make it the centre of Rhodesia’s commemoration of its pioneer heroes. Most spectacular was the burial of the bones of the Alan Wilson Patrol in the late 1890s in a monumentalised grave at Great Zimbabwe, on the order of Cecil Rhodes ‘to await his own death and burial’ (Ranger 1999:30; Kuklick 1991). But these remains were later removed, on the order of Cecil Rhodes’s will, to accompany his own subsequent and heavily monumentalised burial in, and posthumous appropriation of the Matopos Hills (Ranger 1999:30-32, 39-42). Perhaps it was, in part, due to the problematic nature of appropriating Great Zimbabwe as the ancient and exotic heritage of Rhodesia that led to the Matopos Hills being turned into ‘the monumental centre of the white Rhodesian “nation”’ (Ranger 1999:40), and the site of many subsequent Rhodesian commemorative efforts. However, given the well known significance of the Matopos hills to local African peoples, as the site of hugely important Mwari cult shrines (Daneel 1970; Nyathi 2003; Ranger 1999; Werbner 1989), the grave of the great Ndebele leader Mzilikazi at Entumbane, as well as those of earlier, pre-Ndebele rulers (Ranger 1999:19), Rhodesian commemoration in the Matopos must be understood as an appropriation of an already sacred landscape, which was deliberately ‘impressed upon the minds of local Africans’ (Ranger 1999:31, 1987). Ndebele indunas were pledged to guard Rhodes’s grave, and remember their ‘surrender’ to Rhodes in 1896, even as memories of past Ndebele successes in battle or revolt against colonial rule were supposed to be forgotten. As Ranger has discussed (2007) then, if Great Zimbabwe has suffered a lack of ritual and an ‘abundance of archaeology’, then the opposite could not be more true of the Matopos, where cultural heritage and archaeology have been minimal in contrast to an ‘abundance of ritual’, in the form of the Mwari shrines, Rhodesian commemoration at the grave of Cecil Rhodes, and African rituals at the graves of both Mzilikazi and those of earlier, pre-Ndebele Banyubi rulers.

But if Great Zimbabwe did not become the centre of Rhodesian commemoration as it might have done, commemorative efforts did on several occasions continue to surface uneasily at the site. One extraordinary example was the ‘psychic’ séances of H. Clarkson Fletcher (1941) held in the Great Enclosure at Great Zimbabwe in the 1930s, when contact was made with the spirits of several dead Rhodesian heroes, including Alan Wilson and Richard Hall, alongside more ‘ancient’ fictional characters such as ‘Abbukuk’ the ‘high priest’, ‘Utali’ the ‘last of the Queens of Great Zimbabwe’, and of course her lover ‘Ra-set’. But more lasting than these white settler attempts to communicate with the spirits of Rhodesian heroes, was the naming of parts of the ruins after early Rhodesian explorers. Soon after independence, as part of official efforts to rub away any last traces of the colonial, commemorative appropriation of Great Zimbabwe, these names were replaced. The Director of Great Zimbabwe at that time, Cran Cooke anguished about this, suggesting cynically that ‘at some future time Karanga names will be invented or perhaps some areas named after important visitors since independence’ (Letter from Regional Director Cran Cooke to T.Huffman, 11 June 1981, NMMZ File H2). But Cran Cooke misunderstood the continued professionalisation of heritage management that was to follow. Shona terms were allocated alongside neutral English terms for parts of the ruins (like Great Enclosure, Imba Huru, Valley ruins, Eastern ruins, Hill complex) but no parts of the ruins have taken on the names of recent high profile visitors or even the names of famous local or national ancestors. After a Rhodesian pioneer memorial in the nearby town of Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) was defaced shortly after independence, a plaque that marked the site of the removed Alan Wilson memorial grave at Great Zimbabwe also became a subject of controversy, and it was subsequently removed (Fontein 2006a: 170-1).

It was not only the traces of Rhodesian commemorative efforts that were banished from Great Zimbabwe after independence. Expectations that Great Zimbabwe would be elevated to a national sacred site – which emerged from the discourses and spiritual practices of spirit mediums, war veterans, chiefs, and others during the liberation struggle, in tandem with nationalist use of the name ‘Zimbabwe’ as ‘useful rally point’ for the imagination of a new nation – were also undermined and ultimately thwarted by NMMZ (Fontein 2006a: 117-166). The predominance of a ‘heritage’ perspective continued to exclude commemoration of any kind. Immediately after independence, a local medium called Sophia Muchini, who claimed to be possessed by the legendary Ambuya Nehanda, attempted to lay claim to ruins, squatting on site, and carrying out rituals and sacrifices amongst its towering stone walls. Her calls for a national ceremony at Great Zimbabwe, to thank the ancestors for independence, to settle the spirits of dead guerrillas killed and to cleanse the perpetrators of violence, were ignored and eventually she was imprisoned after being implicated in several high profile murders of white settler farmers in the district (2006a: 156 -162). She was not alone in her efforts to campaign for a national cleansing ceremony at the site to thank the ancestors for their support during the struggle. In the early 1980s, another very high profile event was organised, involving chiefs from across the country as well as prominent spirit mediums and members of ZANU PF, during which hundreds of cattle were to be slaughtered in honour of the ancestral spirits (2006a: 40). This event was eventually called off, some allege on the orders of Prime Minister Robert Mugabe himself, and thereafter NMMZ thwarted any further attempt to hold national commemorative or cleansing ceremonies at Great Zimbabwe. In 1985, just as Great Zimbabwe was being considered for the world heritage list, calls for the local district Heroes Acre to be erected within the boundaries of the Great Zimbabwe estate were rejected by NMMZ on the grounds that this was not an appropriate use of a world heritage site9. Even the smaller, localised ceremonies of neighbouring clans, whose historical relationship with Great Zimbabwe was acknowledged if scarcely celebrated or represented, were forbidden by NMMZ after fights nearly broke out between rival claimants from the competing clans of Nemanwa and Mugabe during an early event in the 1980s (Matenga 2000). By the mid 1990s, Great Zimbabwe had indeed become a heritage palimpsest of past activities, and rituals of any sort, commemorative or not, were banned.

But if commemoration of any sort was not permitted at Great Zimbabwe that does not mean the newly independent state did not invest heavily in national commemoration. Indeed just as the last vestiges of Rhodesian memorabilia were removed or sidelined at Great Zimbabwe, so across the whole country the commemorative landscape of Rhodesia was sidelined, and in many cases physically removed, to be replaced by the commemorative symbols and rituals of the newly independent state. Zimbabwe’s postcolonial commemorative project has been hugely controversial in many ways. Kriger (1995) has described in some detail the various controversies that surrounded the high profile removal of Rhodesian monuments in Harare, Bulawayo and elsewhere that followed independence10. But perhaps most controversial of all the Zimbabwean government’s commemorative work has been the National Heroes Acre built in Harare (see figure 2), and the accompanying, hierarchical structure of provincial and district heroes acres across the country that later followed it. Apart from the way in which this memorial landscape has reinforced a particularly Zimbabwean, indeed ZANU PF, kind of elitism – with its grading of district, provincial and national heroes, and in its hard distinctions between the chefs and the povo, the elite and the people11 - this memorial project has also involved a highly politicised nomination process which has been dominated by ZANU PF, and its determination to present the kind of national past that suits its political interests.

National Heroes Acre, Harare

During much of the 1980s, before the unity agreement of 1987 (when after years of violent suppression ZAPU was effectively swallowed by ZANU ) this meant the marginalisation of the role played during the liberation struggle by the other nationalist movement, ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People’s Union) and its armed wing ZIPRA (Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army). As a result, very few ZAPU/ZIPRA heroes have been buried at heroes acre and right up to the unity accord of 1987, ZAPU leaders continued to protest against the ZANU PF dominated process of selecting national heroes, by boycotting national heroes celebrations (Werbner 1998; Kriger 1995; Brickhill 1995). Most famously, Lookout Masuku, the commander of ZIPRA, who had been detained by the government during the ‘arms cache’ crisis of 1982 that later precipitated the ravaging gukurahundi period, was denied national hero status after his death in 1986, despite his well known and huge contribution to the liberation struggle (Brickhill 1995: 164-5)12.

If ZAPU boycotts of National Heroes celebrations during the 1980s challenged the legitimacy of the ZANU PF government’s national commemorative project, then during the same period, the government’s actions also severely hindered ZAPU’s own attempts to commemorate its war dead. As well as the detention of ZAPU leaders such as Lookout Masuku and Dumiso Dabengwa, the confiscation of ZAPU war records meant it was not able to publish lists of its war dead as ZANU PF did on Heroes Days in 1982 and 1983, making the party vulnerable to criticism in the public press (Kriger 1995:151). But much more significant were the military activities against civilians, ZAPU ex-combatants and so called ‘dissidents’ that took place in rural areas across Matabeleland during the gukurahundi period (CCJP 2007), which made any efforts by ZAPU to locate and commemorate its war dead absolutely impossible before the unity agreement of 1987. The urgency of the issue of un-commemorated ZAPU war dead was certainly recognised, and even as the negotiations between ZAPU and ZANU were still in progress, the ZAPU central committee appointed the ZIPRA War Shrines Committee to ‘resume its programme of identifying the ZIPRA war dead’ (Brickhill 1995:166). In the 1990s, its successor, the Mafela Trust began a process of identifying and commemorating ZIPRA’s dead combatants from the liberation struggle, a programme that continues today.

Since the unity accord of the late 1980s ZAPU’s war legacy has been increasingly acknowledged in state commemoration and when Joshua Nkomo, (the former leader of ZAPU, and after unity in 1987, the Vice-president) himself died in 1999 he was buried at the National Heroes Acre in Harare with a record 100, 000 people swarming to pay their respects (GoZ 2000). But the estimated 20, 000 gukurahundi deaths (CCJP 2007:xi) in Matabeleland have never been officially commemorated, and President Mugabe’s apology for the ‘moment of madness’ continues to be controversial and for many inadequate, as Vice President Msika himself implied in a statement in 2006, made whilst attending a Mafela organised event at Jotsholo to commemorate the 1979 killing of 11 ZIPRA cadres by Rhodesian forces (‘Msika speaks out on Gukurahundi’ Zimbabwe Standard, 15/10/2006). Despite the incorporation of ZAPU history into the state’s formal postcolonial narrative, local Ndebele commemorative efforts, both of the liberation struggle and the gukurahundi, continued to be strictly controlled after the unity agreement between ZANU and ZAPU in 1987. As Alexander et al. have described (2000) at some length, two different efforts in Northern Matabeleland in the 1990s to commemorate both ZAPU’s liberation war effort, and the gukurahundi massacres were thwarted after organisers were put under considerable political pressure, and intimidation from CIO agents (2000:259-264). Both a high profile initiative to commemorate ZAPU war dead at Pupu shrine in Lupane – famously the site of not only liberation era violence but also of Lobengula’s last successful stand against the doomed Alan Wilson patrol in 1893 – and a more localised event to commemorate victims of the gukurahundi at Daluka, were subject to ‘heavy-handed obstruction’ which illustrated how ‘the rigid, top-down control of the nation’s “heroes” could not be easily relinquished’ because ‘they symbolized the ruling elite’s legitimacy’ (Alexander et al. 2000:264). Linking either an Ndebele past of resistance to colonial rule in the 1890s at Pupu, or a post-independence past of violence suffered at the hands of the ZANU PF controlled state forces at Daluka, to formal state commemoration of the liberation struggle was unacceptable to the ruling elite, even if that now included former ZAPU leaders13.

Official commemoration at National Heroes Acre has also continued to be beset with problems, despite the government’s incorporation of ZIPRA’s war history in its recent ‘patriotic history’ (Ranger 2004b). Many founding nationalists have been left out of Heroes Acre (and the financial benefits that burial there offers for the relatives of the deceased) as part and parcel of ZANU PF’s determination to control Zimbabwe’s state historiography. The exclusion of Rev. Ndabaningi Sithole (a co-founder of ZANU in 1963 who later became a strong opponent to Robert Mugabe after taking part in the flawed ‘Internal settlement’ negotiations with Ian Smith in 1978) from Heroes Acre in 2000 was particularly remarked upon, causing opposition MPs to question the role of ZANU PF’s politburo in the selection of National Heroes, arguing that ‘hero’s acre did not resemble a national shrine but a ZANU PF shrine’ (‘MPs attack selection of national heroes’ Daily News 2/3/01). The venom of such critiques have been further fuelled by the burial of many ZANU PF politicians and war veterans of dubious national hero credentials in recent years, such as the late minister for youth, Border Gezi, who set up Zimbabwe’s notorious youth militia in 2001; the war veterans Chenjerai Hunzi and Cain Nkala in 2001; and Solomon Tavengwa, a former corrupt mayor of Harare in 2004; to name but a few (e.g. ‘Heroes?’ 21/11/04 facebook.com/Sokwanele-141296717545/). Even former ZANU PF heavy weight Eddison Zvobgo declared in 2001 that ‘the heroes acre we have come to know has lost its glory’ (‘Heroes acre has lost its glory, says Zvobgo’ The Zimbabwe Standard, 19-25/8/01), before his own wife’s death and burial at heroes acre preceded his own subsequent death and burial as a National Hero in August 2004 (‘Obituary’ The Independent, 30/8/04)14.

Apart from the controversies engendered by ZANU PF’s highly politicized control of state historiography and the representation of the past, official commemoration in Zimbabwe has also been beset by problems to do with practices of reburial associated with the structured hierarchy of national, provincial and district heroes acres across the country. Sometimes these had specific cultural dimensions. In the 1980s, as well as protesting against its partisan commemorative project, ZAPU leaders also rejected the government’s 1982 decree that the remains of dead guerrilla fighters ‘that had surfaced from shallow graves dug during the war’ (Kriger 1995:144), should be exhumed and reburied at local heroes acres. Joshua Nkomo argued that Ndebele traditions did not permit the exhumation of the dead, rather they had to be commemorated in their original graves (Kriger 1995:150). As a result, the ZIPRA War Shrine Committee and its successor the Mafela Trust have tended to emphasise the construction of shrines and memorials in situ, rather than exhumations and reburials, ‘except in exceptional cases’ (Brickhill 1995: 166)15.

Although in Shona areas the reburial of dead guerrillas in district heroes acres did sometimes offer meaningful resolution to troubled war legacies – as best epitomised by the 1989 Gutu reburial ceremony described in Daneel’s (1995) thinly fictionalised Guerrilla Snuff – in many cases the hierarchism and elitism of the state’s commemorative project meant that ‘grassroots disinterest in the official commemoration of heroes acres has manifest itself in low party interest in organising reburials, in reluctance to contribute to reburial projects, and in low turnouts at official functions’ (Kriger 1995:148). Rural disinterest in district Heroes Acres also often derived from anxieties about offending local ancestral spirits by burying non-local guerrillas, of different or unknown totem and clan identity, in the areas where they fought and were killed during the war rather than in their own rural areas. While some rural communities have felt ill at ease with the burial of such ‘foreign’ guerrillas in their ancestral territories, living relatives and guerrilla comrades haunted by the spirits of their unsettled dead relatives and friends, have themselves continued to demand the exhumation and return of human remains from shallow and sometimes mass graves in other parts of the country and across national borders in Mozambique and Zambia, to be interred in the soil of their own ancestors and become ancestors themselves (Fontein 2006c:185-188; Cox 2005; Shoko 2006).

A key part of both Ndebele and Shona mortuary rituals is some sort of ‘bringing home’ ceremony, (umbuyiso in Ndebele, or kugadzira or kurova guva in Shona) which involves returning the spirit of the deceased back into the family home a year or more after death, to become protecting ancestors. Failure to perform these specific rituals to return the spirits of the dead, whether involving the reburial of actual remains, or merely the symbolic return of soil from graves elsewhere, is understood to anger and trouble the spirits and in turn precipitate great personal or family misfortune. So it is no surprise that even as official heroes acres have not received the popular support that had been envisaged, demands (which first emerged soon after independence – see Kriger 1995:149) for the repatriation of human remains or symbolic soil from neighbouring countries have continued and have often intersected, in the context of drought and growing political and economic strife, with the demands of spirit mediums, chiefs and others, for a national cleansing ceremony at Great Zimbabwe (or elsewhere) to thank the ancestors for independence, and to cleanse those who fought during the struggle, which I discussed above. These issues gained more national saliency as war veterans became increasingly disaffected during the early 1990s, and subsequently, as their courtship by the ruling party was renewed from 1997 onwards, and particularly in the period since 2000, when Zimbabwe’s political crisis deepened and ZANU PF’s nationalism became increasingly authoritarian (Raftopoulos 2003).

Clearly then, Zimbabwe’s official commemorative efforts have been as controversial as its heritage processes. For most of the independence era, or at least until the mid-1990s, the state continued to maintain a sharp distinction between heritage and commemoration, yet both have involved normalising processes in which particular narratives of the past and particular ways of dealing with its remains have been promoted, while the perspectives and demands of others about the past, and what to do with its remains, human or otherwise, have been marginalised, silenced and excluded. As a result, both official commemoration and heritage have remained problematic and subject to intense contestation.

Liberation heritage

The recent focus on so-called liberation or freedom heritage seems to reverse or challenge this separation between commemoration and heritage. Or perhaps in other words, it seems to exist precisely in the middle of the tension between these two. Originally state memorials and commemoration at Heroes Acres in Harare and across the country were under the control of the Zimbabwe National Army. Since 1994, NMMZ have been officially involved, after it was recognised that the army needed the ‘professional input’ that NMMZ could offer (Interview with C.Chauke 5/4/06). After a lively parliamentary debate in 1995 about the poor state of many Heroes Acres across the country, NMMZ became increasingly focused on answering the ‘deafening call’ for ‘decent burials of our heroes’ and ‘decent heroes acres’16. But it is only since 1997/1998, when former bases at Chomoio (Mozambique) and Freedom Camp (Zambia) were surveyed by NMMZ and formally ‘commissioned’ by the President, that this involvement in state commemorative efforts has been extended to become what is now known as ‘liberation heritage’, involving not only the exhumation and reburial of war dead found in shallow graves within Zimbabwe, but also excavations of former guerrilla and refugee camps in Mozambique, Zambia, Botswana, Angola and Tanzania, and the rehabilitation of mass graves and memorial shrines at these sites17. For NMMZ, as one official put it, ‘the whole issue of liberation heritage has quite a lot of potential importance… as a new direction for us to take’ (Interview with C. Chauke 5/4/06), offering new opportunities in government funding for research and excavations, and reflecting and cultivating a resurgence of renewed public and political interest in NMMZ’s work.

With this growing involvement by NMMZ, it seems that the liberation war, and its material remains are no longer just the subject of state commemoration, but also of formal heritage processes. This is clear from the four phases of the project that were identified by NMMZ’s curator of militaria, Retired Lieutenant-Colonel Edgar Nkiwane, in 2004, which included ‘the identification of the liberation war sites, traditional acknowledgment of the souls of fallen freedom fighters, physical rehabilitation of the burials, erecting memorial shrines and site museums or interpreting centres, as well as conservation and promotion of Zimbabwe’s Liberation Heritage’ (The Herald 18/03/04, cited in Shoko 2006:8-9). NMMZ is now in the process of building a new museum at the National Heroes Acre to contain objects retrieved from its excavations, and to represent an authoritative account of the liberation struggle. At its museum in Gweru, NMMZ already has a display containing objects and photographs from these excavations (Field notes, 26/10/05). Furthermore, NMMZ is also involved alongside the National Archives and the University of Zimbabwe, in a project called ‘Capturing a fading national memory’ to collect oral histories of the struggle. The Zimbabwe National Army has a parallel project collecting such oral testimonies which it has evocatively called ‘Operation mapfupa achamhuka’ in reference to the famous prophesy of the national ancestor Ambuya Nehanda that ‘her bones would rise again’, made when she was hung by Rhodesians after the rebellions against colonial rule in 1896. As one historian at the University of Zimbabwe recently put it, this new drive for the collection of oral histories of the liberation struggle, as well as archaeological excavations of war sites, derives from a recognition of ‘the requirement for there to be a narrative to go along with commemoration’ (G.Mazarire personal communication, June 2007).

Of course, this need for a narrative to go alongside commemoration undoubtedly has serious political dimensions. Indeed this project clearly fits perfectly with the ruling party’s effort to re-imagine Zimbabwe’s past – what Ranger has called ‘patriotic history’ (2004b) – as means of re-asserting its own legitimacy whilst also undermining the ‘liberation credentials’ of the opposition party the MDC. This has also manifest itself in other forms, most conspicuously in a series of controversial and populist ‘cultural galas’ that have been held at sites across the country to commemorate the lives of nationalist leaders such as Simon Muzenda and Joshua Nkomo (see Shoko 2006:4), the unity pact of 1987, and other significant Zimbabwean events. Two very problematic such galas were held at Great Zimbabwe, until pressure from angry local elders assisted NMMZ in their efforts to prevent any further galas at the site (Fontein 2006a: 217-8), and in 2004 one was held at Chimoio in Mozambique, the site of one of the Rhodesian army’s worst atrocities against refugees and ZANLA guerrillas during the liberation struggle18.

But the liberation heritage project can also be seen as a response to a variety of different interests in Zimbabwe and beyond. For many people, the new focus on oral histories of the struggle can offer the opportunity to recount their own experiences, wrestling control of the representation of the past away from both the elite accounts of nationalist leaders, but also those of academic historians who have dominated the study of the war since independence. These oral histories can sometimes offer profound challenges to the dominant narratives of ZANU PF, as for example when rural people describe atrocities and violence they suffered at the hands of both Rhodesian forces and ‘freedom fighters’ during the struggle (Interview with C.Chauke 5/4/06). In other cases war veterans have formed groups like Taurai Zvehondo [lit. ‘talk about the war’], which, according to its leader, the prominent war veteran Cde Rutanhire,

should be a platform where all living fighters and heroes talk about their experiences. We want the unknown ex-combatants whose voices have never been heard, whose stories are still missing, to come forward and participate in this very important event of recording our national history. This is very important because it is the only way future generations will know what really happened

(Cde Runtanhire quoted in ‘Mt Darwin’s killing fields’ Sunday Mail 13/1/2008).

The liberation heritage project also obviously engages with the continuing demands of spirit mediums, war veterans and relatives, for the repatriation and return of the war dead, and the settling of their spirits. The high profile presence of spirit mediums, chiefs and other ‘traditional’ leaders at reburial events in Zimbabwe and abroad19 illustrate the extent to which this project not only merges existing commemorative and heritage structures/processes, but also responds to ritual demands previously marginalised or excluded by both these state dominated processes at Great Zimbabwe, Heroes Acres and elsewhere (Fontein 2006c). In this respect the project can also be seen as part of a wider response to continuing demands for national ritual events to thank the ancestors for independence, and to cleanse the nation’s troubling legacies of violence, which have become more urgent and insistent in recent years in relation to drought, food shortages and economic and political crisis20. Indeed, in 2005 and 2006, the government sponsored nationwide biras in every chiefdom, which according to some were meant to, finally, thank the ancestors for independence, to settle the spirits of the war dead, and to ask for rain (see for example ‘Celebratory biras reach climax’ Sunday Mail, 25/9/05; Fontein 2006c: 185-188; Shoko 2006). Immersed in ongoing and highly complex localised contests, and with Zimbabwe’s macro economic and political situation continuing to deteriorate, it is doubtful whether these events could have forestalled the continuing calls for national ceremonies at Great Zimbabwe or elsewhere; nevertheless they do indicate how NMMZ’s liberation heritage project engages with ‘traditionalist’ concerns across Zimbabwe. It is equally important to note that the liberation heritage project has not been entirely monopolised by spirit mediums and other adherents to so called ‘traditional’ religion; representatives of churches and in particular prophets from African independent churches have also been involved, as exemplified by the role played by a prophet called Jimmy Motsi in the location of war graves in Mt Darwin (‘Mt Darwin’s killing fields’ Sunday Mail, 13/1/08).

For NMMZ, this new liberation portfolio also came precisely at a moment when it began to take seriously and implement a new interest in the intangible, living and spiritual aspects of heritage. This has manifest itself in the easing of restrictions against local ceremonies at Great Zimbabwe, and even an NMMZ sponsored event to reopen a sacred spring in 2000; a growing concern to involve local communities in the management of all of its heritage sites; and the successful world heritage nomination in 2004 of the Matopos hills as a cultural landscape, thereby recognising the huge spiritual significance of the Mwari shrines of Njelele and Matonjeni, and the grave of Mzilikazi, founder of the Ndebele nation. Whether these important changes to NMMZ’s approach to cultural heritage derive from UNESCO’s determination to overturn the monumentalist and Eurocentric biases of its world heritage concept as originally encapsulated by the World Heritage Convention of 1972 (see Fontein 2000) or if the reverse is true (that changes to the world heritage system were provoked by the experiences and demands of practitioners in African states and elsewhere), is hard to say and perhaps beside the point. What is clear is that the broader, international climate of changing definitions of world heritage, an increased recognition of ‘intangible’, ‘ritual’ and ‘living’ forms of heritage, and a mounting desire for notions and practices of world heritage to be responsive to both African contexts, and particular ‘local’ forms of management, provides the context within which Zimbabwe’s liberation heritage project gains traction across the southern African region. Although it undoubtedly fits well with ZANU PF’s own ‘patriotic history’, the saliency of ‘liberation heritage’ both across the region and for UNESCO should not be understated. This is evidenced by the substantial co-operation between the national heritage organisations of individual states in the region (particularly between Zambia’s National Heritage Conservation Commission and Zimbabwe’s NMMZ), between SADC countries as a whole, and by the role of UNESCO’s Windhoek office in this programme21. The significance of the international dimension of the NMMZ’s liberation heritage project is also revealed by the existence of other related regional programmes such as ALUKA’s ‘Struggles for Freedom in Southern Africa’ project, which is creating a digital library of oral and archival sources on anti-colonial movements in the region (see www.aluka.org/).

There is also a sense in which this new liberation heritage project is a response to events already happening on the ground. Apart from collaborating with the ongoing work of two prominent NGOS in Matabeleland, the Mafela Trust and the Amani trust, NMMZ is also working with the War Veterans Association which has an obvious interest in the project. Cox (2005) and Shoko (2006) both describe events that followed the discovery in 2004 of mass graves containing the remains people killed by Rhodesian forces in the Mt Darwin area of north-eastern Zimbabwe. Here war veterans along with relatives, spirit mediums, and in some cases members of the CIO, led efforts to locate, identify, exhume and rebury individual human remains from mass graves. In some reported cases, the spirits of the dead themselves were involved as they possessed spirit mediums or war veteran comrades, and were then able to identify their own specific bones from the remains of the estimated 5000 people buried in the 19 graves and abandoned mines in the area (see Shoko 2006 & Cox 2005). In January 2008, Taurai Zvehondo and another war-veteran-led organisation, the Fallen Heroes Exhumers, which have both been involved in identifying mass graves in Mt Darwin, were reported to be ‘awaiting assistance from the Government which should lead the exhumation process’ (‘Mt Darwin’s killing fields’ Sunday Mail January 13/1/2008; ‘Efforts to locate 2nd Chimurenga mass graves continuing’ ZBC News, 12/1/08). Similarly in 2006 Crispin Chauke, then acting deputy executive director of NMMZ, described how local people had reported the existence of a site called Chomungai on a re-settled farm in Gutu, where more than 100 people died during the war and requested ‘some sort of museum or memorial to be built there, and NMMZ are involved in that’ (Interview with C.Chauke, 5/4/06). NMMZ have also been involved in singular burial sites were the identity of the individual concerned is known to local communities. In Chivi people reported a site to NMMZ where the bones of a guerrilla fighter buried during the war ‘are now visible, and there will have to be museums intervention at that site’ (Interview with C.Chauke, 5/4/06).

As well as working closely with war veteran organisations and local communities, NMMZ also works with the families of the unsettled dead themselves, who sometimes approach them asking for help in identification, exhumation and reburial of their dead relatives. Crispin Chauke described a reburial that took place at the request of a close relative of a man killed by a landmine in Gaerezi in eastern Zimbabwe. In that case, the dead person’s identity and the details of his death were known by witnesses, but in many cases local knowledge about the identity of dead guerrillas is limited to the noms de guerre that guerrillas adopted during the struggle to ensure the safety of their kin. Such problems are frequently confounded in cases where people were buried far away from their own home areas, such as in camps in Zambia and Mozambique, or in distant operational zones within Zimbabwe. It is perhaps exactly in such cases that the role of prophets, n’angas and possessed spirit mediums come into their own, complementing both the collection of oral histories and the forensic archaeological approaches that NMMZ and organisations like Mafela and Amani are involved in. In some of the cases described by Shoko (2006) and Cox (2006) it was the living relatives themselves (in one case a 14 year old girl) who, possessed by the restless spirits of their dead brothers and children, have located, named and identified the particular bones of their relatives to be returned and buried into the soil of their own ancestors in their own rural homes.

Although there are some obvious continuities with previous state commemorations and reburials (eg Daneel 1995), it does seem, then, that this new ‘heritage’ project has much more potential to deal with the complex, overlapping demands of the dead themselves, and those of living relatives, war veterans, and others haunted by them, than that afforded by the highly problematic commemorative efforts of the 1980s and early 1990s. This does not mean that the new project has not been contentious. Some spirit mediums I spoke to in Masvingo District in 2006 derided both the national bira ceremonies held in September 2005 and the reburials carried out at former camps in Mozambique for being politically motivated, or for not following correct procedures or involving the proper ancestral representatives (e.g. Fontein 2006c: 186-7). Of course, like nearly all such ‘traditional’ events in Zimbabwe, these reburials are subject to the different interpretations, political and clan loyalties, and religious beliefs of people involved. It is also unclear exactly to what extent NMMZ (and the other national and international bodies involved, not to mention the ruling party) will be able to continue to allow the rather adhoc involvement of war veterans, spirit mediums, n’anga’s, prophets and relatives in these reburials, without stamping some of its own more conventional, bureaucratic imprint upon the processes. Nor is it clear to what extent NMMZ is able to successfully deal with the intensely troubling legacies of Zimbabwe’s gukurahundi (cf. Eppel 2004), commemorations of which, as I mentioned above, have been subject to particularly stringent control since 1987.

Nevertheless it does seem as if NMMZ’s new liberation heritage project is qualitively different both from past state commemoration, and the professionalised heritage processes that have been so problematic at Great Zimbabwe and elsewhere, regardless of the fact that this does not mean it is any less politicised or controversial. NMMZ’s liberation heritage project does seem to be located exactly in the middle of the tension between commemoration and heritage because the reburials of the war dead have involved both the distancing, ‘objectifying’ and ‘professionalizing’ processes of heritage and archaeology, and efforts to respond to the demands of war veterans, traditionalists and kin, and even of the dead themselves, to be commemorated, memorialised, and ritually ‘returned’ to Zimbabwe, and to the soil of their ancestors. In short, the reburials have involved both efforts to narrate and objectify the past, and efforts to respond to the demands that the dead make on the living. In Chauke’s words:

We try to combine both forensic methods and traditional methods. At Nyadonzya [Mozambique] for example we had traditional people come there because it was felt that the spirits of the people killed were still there and needed to be returned to their home country. So the chiefs were sent there….So they went to all the different burial sites at Nyadonzia and did rituals there and collected soils to be brought back to Zimbabwe so that the spirits could return home. Some of these soils are now in the tomb of the unknown soldier, to represent or take the spirits of the dead child back to his home country.

(Interview with C.Chauke 5/4/06)

Above all else, then, it is its effort to respond to the demands of the dead which marks this project out as different from both the distancing effects of previous heritage processes and the earlier, problematic state commemorations of the 1980s and early 1990s. Pushing this analysis further in the last section of the paper, I want to reflect briefly on how apart from, or rather in conjunction with, the spirits of the dead, it is the bones and physical remains of the dead, in their very presence and materiality, surfacing from the soil of shallow graves across the country and over its borders, that have subverted the otherwise normalising aspects of commemoration and heritage in Zimbabwe.

Unsettling Bones

If both heritage and commemoration in Zimbabwe have involved the marginalisation of alternative pasts and alternative ways of dealing with its material remains, then bones have often confronted and subverted these normalising processes. Building on the work of Howard Williams (2004) and others (e.g. Hallam & Hockey 2001; Tarlow 2002; Verdery 1999; Hertz 1960), I suggest that it is through their ambivalent agency as both ‘persons’ and ‘objects’ that bones can do this. The most obvious way in which bones can confront both commemorative and heritage processes is through the presence of the ‘wrong’ bones (or indeed the absence of the ‘right’ bones) which point to alternative versions of the past otherwise silenced or forgotten. At Great Zimbabwe, the presence of local African graves of the recently dead of the Mugabe clan who occupied the site when Cecil Rhodes’s pioneer column entered the country in 1890, proved to be a profound challenge to the antiquarian fantasies of colonial apologists, but provided no more comfort for the ‘professional’ archaeologists aligned on the other side of the Zimbabwe Controversy either. The recent date of the graves made them irrelevant for archaeological interests that were mainly concerned with identifying the 12th -15th century occupiers of the site. The continued failure to find graves, tombs and human remains dating to that period continues to confound archaeologists, much as the absence of any sign of ‘ancient’ ‘exotic’ remains frustrated the antiquarians before them.

More recently, the presence of these local graves has begun to unsettle the otherwise comfortable predominance of archaeologically informed heritage managers. For members of the Mugabe clan, the presence of the graves of key ancestors at Great Zimbabwe has been the basis of their claims to the custodianship of the site, and their efforts to gain access in order to carry out rituals there (Fontein 2006a: 30-4). As NMMZ has increasingly adopted in-vogue notions of intangible, living and spiritual heritage, the presence of these graves, and the other local claims to the sacred importance of Great Zimbabwe, has meant that NMMZ has had to reconsider the archaeological pre-occupation with the particular ‘black-boxed’ (Hodder 1995:8) dates of Great Zimbabwe’s medieval construction and occupation. In a sense, then, these graves – the material presence of these ‘wrong’ bones – have confounded and provoked profound challenges to the distanced, professionalized view of Great Zimbabwe as a national heritage site the only relevant past of which lay in the 12th to 15th centuries, forcing its heritage managers to engage with the hitherto silenced history-scapes of local clans (Fontein 2006a:19-45).

Whilst the presence of the graves has also featured prominently in widespread efforts to claim ancestral ties to land occupied and resettled in the context of recent land reform (Fontein 2006d & 2007; also Shoko 2006), bones have also confounded, at different moments, the highly politicised commemorative efforts of the Zimbabwean state which I discussed above. As Kriger (1995:144, 149) described, one of the issues that affected earlier state–directed efforts to rebury the remains of the war dead at the district and provincial heroes acres, was determining which bones were which. In many cases, dead guerrillas, Rhodesian soldiers, and auxiliary government forces were buried together in anonymous graves. This caused problems for rural people tasked by government to rebury the remains of war dead that were resurfacing from shallow graves. Even President Mugabe realised this problem when he made a statement to the Zimbabwean Parliament in 1986 asking ‘how do we distinguish good bones from bad bones, the heroic ones from the fascist ones and so on’ (Kriger 1995:144).

But in terms of the ‘wrong’ bones, much more problematic for the government has been the resurfacing of the bones of victims of the gukurahundi massacres in Matabeleland in the 1980s22. These other ‘wrong’ bones could easily amount to a profound challenge to the ruling party’s efforts to present a particular and narrow version of the violent struggles that followed independence in 1980. Although the two efforts described by Alexander et al. (2000:259-264) in Matabeleland in the 1990s to promote the commemoration of other, silenced histories, were thwarted, the bones of the gukurahundi victims like those of the liberation war dead, keep on re-surfacing from shallow individual and mass graves and abandoned mines in Matabeleland and across the country – confronting and challenging the efforts of the state to control representations of the past, and straining the precarious unity of former ZAPU and ZANU factions in ZANU PF23. In 2005, before his more recent intimacy with the hard line inner core of Mugabe’s regime, Jabulani Sibanda, the leader of the war veterans association, acknowledged that, ‘he too would like to see the perpetrators of the massacres tried in international courts’, as reports emerged of plans being prepared for reburials and cleansing ceremonies to take place ‘once Mugabe leaves office’ (see ‘Mass graves from the Gukurahundi era located in Matabeleland’ SW Radio Africa Zimbabwe News, 19/10/05; also Eppel 2004:57). Yet to a limited extent, the location and identification of gukurahundi remains have already been taking place. One contact at NMMZ acknowledged that many, if not most, of the exhumations and reburials that they have been involved in Matabeleland have been gukurahundi victims. But, as I was told, ‘this is very sensitive. VERY SENSITIVE. The gukurahundi stuff is never talked about’ because ‘people are afraid to open up old wounds…especially …because at one point nearly the whole of Matabeleland was MDC’ (Interview notes, 2006). The horrific memories of the gukurahundi massacres are too recent, too emotive and too political, challenging the precarious unity of ZANU PF in Matabeleland. And indeed since this paper was first written, old ZAPU elements within ZANU PF have now formally withdrawn from the unity agreement of 1987 to reform ZAPU under the leadership of Dumiso Dabengwa (‘Zapu Breaks From Zanu PF’ Zimbabwe Standard 16/5/2009), who has insisted that ‘true national healing in Zimbabwe can only be possible when President Robert Mugabe apologises for the 1980s Matebeleland atrocities perpetrated by his government’ (‘Dabengwa says Mugabe must apologise’ 12/5/2009).

More recently, the emerging and re-surfacing human remains of victims of the ruling party’s violent excesses against opposition supporters since 2000 – such as the death of Gift Tandare with which I began the paper, or the three bodies found at Kariba Dam by engineers in April 2007 (‘Zimbabwe: ZESA Engineers recover three bodies from Kariba Dam’ www.zimdaily.com, 12/4/07), or the stench of the 20 decomposing, still unburied and unidentified corpses of MDC supporters dumped in an Nkayi morgue in 2002 (‘The revenge of the dead’ Zimbabwe Today, 13/3/08), or the hundreds of opposition supporters killed during the election violence of 200824 – confront ZANU PF’s current claims about where responsibility for recent political violence lies. It is likely in the future that the unsettled dead of Zimbabwe’s most recent violence will return in their demands for reburial, cleansing and commemoration, just as the spirits of ZANLA’s and ZIPRA’s dead guerrillas and the victims of the gukurahundi continue to demand commemoration.

If these examples illustrate how bones and bodies can confront heritage and commemorative processes by retorting silenced or marginalised pasts back to the present, contesting or undermining the dominant narratives of political elites or heritage managers, bones and bodies can also problematise heritage and commemoration in other ways that have less to do with representations of the past, and more to do with what I call, tentatively, their emotive materiality as human substance, and their affective presence as dead persons or spirits or subjects that continue to make demands on society. It is pertinent to note, in this respect, that it was the stench which drew attention to the 20 decomposing corpses in the Nkayi morgue, and the ‘out of place’presenceof bodies which did so at Kariba dam or in the mines of Matabeleland, the Midlands and Mt Darwin, and similarly the resurfacing of bones in the villages of Dembezeko and Nyamanja in Mt Darwin as farmers tilled their fields after rains in January 2008.

Although there has, in recent years, been a growing interest in the agency of objects (cf. Miller 2005:11-15), bones and human remains often continue to be ‘understood only as a set of materials without agency or the ability to affect the actions and perceptions of the living’ (Williams 2004:264). This approach fails ‘to appreciate the close entanglement of the living with the dead in many societies…[and] in turn it underestimates the complex engagements between people (both living and dead) and material culture in the production and transformation of social practices and structures’ (Williams 2004:264). The importance of Verdery’s contribution (1999) here is that she initiated the exploration of how dead bodies animate politics in complex ways, yet ultimately her focus is limited to the ‘symbolic effectiveness’ of human remains for the politics of the living. What I want to suggest here, by way of conclusion, is that there is a need to complete the process of de-centering the agency of living human subjects in order to further explore how the political efficacy, and indeed agency of the dead, is closely related to the emotive materiality and affective presence of bones and human remains, and is not, therefore, limited merely to the symbolic.