"I don't wan' it smooth, like salsa, I want a harsh sound bro":

Negotiating a rap sound in Cuba

Author: Bastien Birchler, Institute of Anthropology, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Date: 21/08/2011

html / PDF

ISSN 2073-4158

Abstract

In Cuba, music is celebrated as a key element of Cuban culture and as a distinctive feature of Cuban cultural identity. Accordingly, music constitutes a privileged site to investigate the production of discourses on national cultural identity. This article tackles these issues by focusing on the negotiation of a rap sound in Cuba. In recent years, complex processes of institutionalization have taken place aimed at integrating rap music into the official Cuban cultural field. While several important contributions have been written on the subject, most studies downplay the musical dimension of rap by seeing it primarily as a social movement with negligible musical qualities, thus threatening to reduce this phenomenon to a textual expression. An ethnographically grounded examination of musical production and related processes helps redress this bias, shedding new light on the negotiations taking place between a group of rappers and institutional agents in charge of cultural promotion politics. This approach highlights major discrepancies in conceptions of an authentically Cuban sound, unpacking what is at stake in notions of “cubanity” and “underground-ness” while illuminating their competing interpretations.

Keywords: Music, Identity, Cultural Policies, Underground, Cuba

You can comment on this article on a specific page of our blog.

Article title

Contents

Rap in Havana and the controversy on its “cubanity”

The promotion of Cuban rap: institutional policies

The musical production of an “underground” collective

Challenging “cubanity”

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

Author information

Introduction

This article focuses on the negotiations that surround the forging of a rap sound in Cuba. Rap is a musical genre that emerged on the island in the early 1990's, at the time of the crisis brought about by the collapse of the communist block, Cuba's principal ally. During this period of economic crisis, important changes took place in Cuba. Overnight, Cubans’ standard of living collapsed. Basic foodstuffs were scarce. Fidel Castro named this historical moment “the special period in a time of peace”. The crisis had a profound influence on the organization of Cuban society and led to major changes in the everyday life of Cuban people.

Today, the living conditions that characterized the “special period” have noticeably improved, due in particular to the development of new strategic alliances with the left-wing governments in Latin America, many of whom have close ties with Cuba. However, the regime’s foundations remain undermined and the president, Raul Castro, has publicly recognized the dysfunctional nature of the current system (Habel 2009).

Like timba1, rap music is often presented as “music of the crisis”, (Fernandez 2003a ; West-Duran 2004 ; Perry 2004 ; Baker 2005, 2006), thus linking the emergence of this phenomenon to the specific socio-historic context of the crisis. When rap first emerged in Cuba, the rappers were recognized for their critical discourse concerning Cuban society. They considered their music to be a protest music (música de protesta). The large majority of rappers were black and they addressed social issues(temas sociales). The existence of racial discrimination and the growth of inequalities in a communist society that portrayed itself as based on the equality of all citizens were among the key issues at stake.

While addressing the specificities of rap music, researchers generally depict this phenomenon as "socio-musical", but focus their attention only on the "socio" part of the assumption. To consider rap as discourse - as simply a textual contribution - ignores the "musical" dimension, which we find expressed not only in its spoken rhythms but also in what my informants in Cuba themselves qualified as “music”: the instrumental accompaniments that make the focus of this article. The neglect of rap’s musical dimensions may result from restricting too narrowly the focus of attention to the act of speaking, which is certainly one of its key features but should not obliterate other important aspects. According to Pecqueux (2005), the act of speaking in rap is characterised by the way the rapper poses as interpreter as well as composer and protagonist. This "uniqueness" of the rapper's persona provides his discourse with a form of legitimacy unlike other forms of popular music, which are less concerned with giving an account of reality. Furthermore, Pecqueux stresses the collective dimension of speech in rap. The rappers frequently pretend to convey the voice of the voiceless and then "represent2 them" (according to the usual wording). I would argue that this form of legitimacy based on talking about reality3 and representing a community reinforces the tendency scholars have to look at rap as a sociological discourse. According to Geoffrey Baker, scholars who study rap in Havana generally see it only as a “transparent discourse”, one that is politically elaborated. He acknowledges that studies have centered exclusively on the rappers’ texts, leaving aside other significant aspects of rap production such as the geographical inscription of rap within the city or the conditions in which the performances take place (2006:218).

In a deterministic manner, rap is reduced to a discourse that reveals socially sensitive issues (such as the emerging consciousness of black identity) and is perceived as an ideological battlefield in which the rappers' texts provide a framework rooted in the realm of profane sociology. Hennion (2005) is among the few scholars to point out the problematic character of this socio-centered approach to rap. As he puts it, the problem is that the discourses of rap scholars risk being conflated with those of the rappers themselves:

The commentaries of the specialists (rap scholars) give the impression of only repeating- but in a heavier manner and taking them without the required analytical distance - the analyses of the rappers themselves, while the sociologist, used to deal with the aesthetic and usually anti-sociological discourse of amateurs, is caught off guard by this explicitly sociological discourse (2005: 130, my translation).

As Pecqueux has shown, this problem results first and foremost from the biased perspective with which scholars focus on rap. By considering rap as a purely sociologically/politically articulated discourse, they neglect other aspects, which would be helpful in understanding this phenomenon. Pecqueux chose, for instance, to root his analysis of rap in the field of popular song (Pecqueux 2003).

Building on these critiques, I focus in this article on what rappers in Havana call “musical production”: the musical accompaniment produced by rappers, which serves as background for their lyrics. As revealed by the recent history of rap in Cuba and the debates that surrounded its emergence, the alleged “lack of cubanity” of rap’s musical dimension sometimes prompted the resistance of the Cuban authorities to the integration of this genre into the national musical field. In the first part of the article, the analysis of controversies on the “cubanity” of rap music shows how issues of cultural and national identity are at the core of musical debates in this Caribbean island. This enables me to start unpack what is at stake in the elaboration of a "sound identity" for rap in Havana. Paying particular attention to the issue of musical production, and relying on interviews with state promoters, I will scrutinize the central themes of the policies promoting rap. Moving from the institutional perspective to that of rap producers, in the ensuing section, I consider the musical production of a rap group that I studied during eight months of ethnographic fieldwork in Cuba in 2005 (Birchler 2008), and which was among the most active in the Havana Rap scene at the time. My analysis of their discourses and practices regarding musical production shows how the group’s members elaborate their own criteria to justify the legitimacy of this originally North American phenomenon. This leads me to discuss representations of “cubanity” through the prism of the rap musical genre, in a context characterized by a period of crisis, and enables me to develop a broader reflection on the representations and display of a Cuban cultural identity in the musical field.

Rap in Havana and the controversy on its “cubanity”

Rap music spread in Havana in the early 1990’s, coming from the “enemy country”, the US. Young people began creating makeshift antennas in order to pick up American radio programs that aired this new musical style. The aura of subversion surrounding this phenomenon undoubtedly played a role in the craze that it sparked off. By 2000, several hundred groups existed in Havana. On every street corner, dance steps, picked up from American television programs via illegal satellite disks, were being performed. In a second phase of its development, the Cuban authorities themselves started promoting rap music. Indeed, rap has been subjected to a process of integration into the national cultural field, a process that Baker calls the “nationalization of Cuban rap” (Baker 2005).

Focusing on the musical production of rap in Havana, I observed tensions surrounding its integration into the Cuban musical field. Indeed, there is a recurrent tendency amongst scholars to question the “cubanity” of this phenomenon by casting a doubt on the compatibility between this genre and a supposed "Cuban musical tradition", whose main features I will scrutinize later in the text. Basso Ortiz (2001), a scholar working on Cuba, wonders for instance if one can really consider rap to be a Cuban cultural manifestation possessing its own characteristics that differentiate it from American rap or rap from other countries. In an article tellingly titled “Time to open the eyes, Cuban rap does exist!” (Hora de abrir los ojos… ¡El rap cubano si existe!), Grisel Hernandez (Casanellas & Hernandez 2002), a Cuban musicologist, tackles these very same issues, before concluding that Cuban rap does exist. As this controversy suggests, the “cubanity” of rap is a key issue capturing peoples attention, one that absorbs much of the contemporary debate surrounding this musical genre. Stemming from this preoccupation, Hernandez introduces a distinction between a form of rap produced in Cuba on the one hand, and Cuban rap on the other. Ariel Fernandez Diaz, a young promoter of rap who has written several articles on the subject, also comes back constantly to this question of the “cubanity” of rap. He concludes that rap in Cuba was originally characterized by its proximity to US rap, before it became a true Cuban cultural expression (Fernandez Diaz 2000, 2002). While arguing for the recognition of rap, Fernandez Diaz also becomes enmeshed in the rhetoric of authenticity.

Given that the subjects treated in the rappers' discourse deal almost exclusively with local issues (and thus cannot be considered simply as a US import), and that rappers proved the poetic value of their production, all the previously mentioned authors acknowledge the textual contribution of what they recognise as Cuban rap. What remains contentious is the autonomy of the musical production, which has been repeatedly called into question. This conception implies that such music could only be an imitation of the original US source. It denies the rappers a creative posture under the pretext that they simply recycle existing pieces of music. These views tend to elude the fact that as "original" a musical creation might be, it always implies processes of citing, repetition and re-appropriation. According to these critics, the rappers have not been able to find a way to “nationalize” their production, that is to say to "cubanise" it.

But what is implied in this idea of cubanity? What is the connection between music and “cubanity”, between “Cuban musical tradition” and national identity? In her book “Musiques cubaines”, Maya Roy considers “cubanity” to be the cultural translation of national identity (Roy 2001: 9). In this sense, the question of “cubanity” that I am addressing through the example of rap is directly linked to that of Cuban national identity in the context of the present period of crisis. This question becomes even more significant once we consider that music plays a prominent role as a marker of identity in Cuba. Indeed, Cuban music is today praised as one of the country’s major cultural specificities, one of the top sites where the Cuban process of mestizaje finds expression. In this respect, people in Cuba repeatedly told me about the son (frequently considered as the national music, that later gave birth to salsa) as epitomizing the successful union between African percussion and Spanish guitar. Son, and more generally the overarching image acquired by Cuban music, tends to crystallize the idea of a mixed identity, an idea praised and promoted by the elites and largely shared by the wider population.

Historically, De la Fuente (2005) has shown that the Cuban elites who contributed to the foundation of the Cuban nation adhered to an ideology of "racial democracy" in opposition to European racist influences of the 19th century. Through this ideology, they tended to consider (at least at a discursive level) racial diversity and metissage not as a defect but as a richness4 (De la Fuente 2005). In the 20th century, the key figure of Cuban anthropology Fernando Ortiz pioneered research on cultural contacts by studying the different groups that made up the Cuban population. Ortiz was one of the first scholars to pay attention to black people in Cuba and to valorise their cultural traits. He developed the notion of transculturation to account for the reciprocal influences between two cultures in contact. Among Ortiz's main focuses was the study of music, and nowadays his work on the matter is still highly considered in spite of a lack of theoretical systematisation and some dubious assertions on European cultural superiority (Moore 1994). Ortiz was firmly committed to a cultural defence of nationalism, and his warnings against the threat of cultural imperialism coming from the USA may explain why his work continues to be influential today (Froelicher 2005) in a country where the idea of cultural resistance through music has been present in all musicological thinking since the Revolution of 1959.

If we look at Cuban popular music nowadays, we can see indeed that it largely conveys a positive vision of metissage as something Cubans should be proud about. The song "Somos cubanos" (We are Cubans), from the legendary band Los van van, is a good example of this state of affairs. In the song, the singer reviews the genealogy of Cuban people emphasizing its different ingredients, before claiming with a strong sense of humour: "Somos la mezcla perfecta, la combinacion más pura" (We are the perfect blend, the purest combination). This last sentence, which links the notions of purity and combination, perfectly illustrates local attempts to re-define the symbolic associations regarding mestizaje in Cuban discourse. Accordingly, the notion of purity - usually employed to single out separate entities - is here appropriated to valorise on the contrary the mixing of influences.

Following Froelicher, I would argue that this view of a new original mixture resulting from the encounter between distinctive elements can be considered as a "myth of origin of the Cuban nation and its music". These features would constitute its "essence", "an essence that keeps the music open for exterior influences which accordingly can be easily adopted and nationalized" (Froelicher 2005). Thus, we may argue that since the Revolution of 1959, the Cuban authorities’ attitude toward foreign musical influence has been oscillating between fear of cultural invasion and a strong confidence in Cuban music's capacity to absorb and somehow nationalise influences.

On the one hand, the authorities’ fear found expression in censorship policies put in place toward new musical trends like rock'n'roll, jazz, salsa, which were accused of conveying immoral capitalistic values or decadent bourgeois conceptions, while ‘hippie’ music was seen as a threat due to its association with drugs and the challenges it posed to the very idea of work (Manuel 1987; Roy 2001; Moore 2002). On the other hand, the Cuban authorities also trusted Cuban music's capacity to assimilate or absorb foreign influences thanks to a process of "cubanisation", a process able to neutralize the potential danger they represented to Cuban culture. It is in this sense that in his book From the drum to the synthesizer, influential musicologist Acosta writes about the “cubanisation” of different foreign musical influences that reached the island, such as rock'n'roll, jazz or salsa (Acosta 1987). Regarding rock music, another musicologist, Argeliers, argues that "rock imported to Cuba loses its negative features, for the alleged commercialism, hedonism, and excessive individualism of rock are extra-musical features, dependent upon their cultural milieu and dissemination" (cited in Manuel 1987:164). What appears here is the author’s strongly held belief that local cultural features allow Cuban music to avoid what is perceived as ideological contamination.

As I show in the following sections, the intersections between music, nationalism, and cultural identity become extremely relevant also when considering the production of rap music in this Caribbean island. First, I will turn my attention to the promotion of rap in Havana and - through interviews with promoters of this genre - describe how it is considered from a musical perspective.

The promotion of Cuban rap: institutional policies

I shall begin by considering briefly the policies put in place by the government for the promotion of rap, in order to see to what extent this genre was accepted and how, in musical terms, its integration into the Cuban cultural field has been dealt with by the authorities. The analysis will draw on extracts of interviews with representatives of the two major institutions promoting rap in Havana.

From the mid 1990’s, the Cuban state began to actively promote rap through a cultural institution - the Hermanos Saiz Association (AHS) - that originated from the powerful Communist Youth organization. AHS was the first institution to get involved in the promotion of rap, officially recognizing the rappers' status and shaping the "Habana Hip-hop" festival, the main rap event in the country, which first started as a street corner happening. It was within this association that a dialogue emerged between rappers and representatives of the state. This process led to the recognition of rap as a “revolution in the revolution” (Perry 2004: 226) and the consideration of rappers as part of the “revolutionary vanguard”. At this point, one must ask what generated such a positive response and acceptance of rap by the Cuban institutions and what led the authorities to elevate it to the rank of exemplary cultural phenomena. To understand this, it is important to asses how rap was initially perceived by Cuban officials.

Beginning in the 1970’s as a niche phenomenon limited to a few neighbourhoods in the city of New York, rap has today become a global phenomenon, generating huge incomes in the international music industry. In the media, rap is partially associated with the validation of ostentatious consumerism, one in which the figure of the rapper businessman occupies a central position (Cachin 2001). At the same time, a fringe group of rappers have voiced their determination to stay out of the “mainstream”, refusing the commercialisation of their practice and insisting upon the need for rap’s independence from “systems”, either economical or political, that could influence its content. Representatives of what is called “underground rap” generally criticise capitalism, neoliberalism and other logics of the market economy perceived as degrading. Thus, several North American rappers, for instance, regularly call upon revolutionary imagery.

Cuban cultural officials have been won over by this "underground rap" that embodies a revolutionary counter culture. Alpidio Alonso Grau, head of the AHS, declared the festival to be a "symbolic" event uniting Latin American countries against U.S. imperialism under a Cuban banner (cited in Baker 2005: 391). The Cuban government has a long history of supporting US actors critical of their own government policies, following the rationale that “my enemy's enemies are my friends.” For instance, Cuba welcomed and gave political asylum to several members of the Black Panthers wanted by the US authorities. Two of these personalities, Nahanda Abdioun and Assata Shakur, have worked from Cuba to build connections between the American underground rap scene and the Cuban rap scene (Perry 2004: 183).

As a result, the rap scene in Havana had generally been considered as “underground” by the different actors involved in it. During an interview, Hilda Landroe Torres, director of the Havana branch of the AHS, argued that the goals of the rap movement corresponded perfectly with the state ideology. Thus, she applied the word “underground” employed by rappers to the revolutionary ideology:

Generally speaking I would say that Cuban culture is itself an underground culture. It's a country where people go against the grain; by definition it is in some way a rappers' country. And by its very nature it also participates in the dynamics that the Hip-hop movement can have, a movement that is, generally speaking on the political left, and that defends equality and improvements in society, so that society's plagues will disappear. Isn’t that so? And the revolution shares the same objectives. So obviously they must coincide on a number of questions.

Her perception of rap had the tendency of neglecting the musical dimension of the phenomena in favour of a view of rap as discourse concerning society. When I asked her how she considered rap from a musical perspective, she replied:

I don’t believe that this movement is essentially musical. I think that it is a movement that expresses itself, in one of its variations, through music. But music remains an instrument for conveying the text.

Later on, we discussed the attempts made by certain rappers to work out musical fusion, particularly with reggaeton5. She then expressed her great distaste for this type of music, which she accused of “contaminating” rap:

Where reggaeton contaminates rap, is in the fact that rap comes with all its social preoccupations that are expressed by the rapper. And reggaeton, independently of whether it is good or bad from a musical point of view (and for me personally, it is very bad, but aside from that) reggaeton avoids any social concerns, it doesn’t question anything, it’s simply music to dance to, isn’t that true? And by contaminating rap, it takes away the preoccupation that during its ten years of existence has been its principal motor, isn’t it?

In Torres’ words, rap is perceived as a speech that uses music as a resource but that has value only when it deals with social problems stemming from the everyday life of its protagonists. Thus, reggaeton becomes an aberration, the antithesis of rap.

Following the international success in 1999 of the rap group Orishas, some of the structures promoting professional music, known as “musical enterprises” (empresas musicales)6, started working with rappers. In 2002, a further step was taken when a specialized institution, The Cuban Rap Agency (ACR) was created in order to promote quality national rap. By means of this active promotion in different institutions, the state has been able to play a significant role in defining what rap should or should not be. However, as Baker has pointed out, there is no unity in the way the state institutions approach rap:

The Cuban state cannot be considered as a monolithic entity: it incorporates divergent ideological tendencies, and this lack of uniformity is reflected in the cultural policies (Baker 2005: 371).

The Cuban Rap Agency was set up in the mode of the “empresas musicales” in order to professionalize a small number of rappers. Thus, it was as a musical product that rap was taken into consideration. During my fieldwork in 2005, the ACR was made up of only eight groups. This represented a tiny percentage of the existing groups in Havana. Furthermore, five out of eight had turned to reggaeton, a far more successful formula than rap from a commercial point of view. When discussing the criteria of quality that allowed her to evaluate the musical production of rap, Grisel Hernandez, a musicologist working at the ACR argued:

Let’s see. At a certain moment, I think that rap was rather mimetic (with the US rap) because of the lack of material to make the backgrounds7. Thus, they used all these backgrounds coming from North America to rap on. That was at the beginning. Then came a time when the rappers themselves said that they weren’t satisfied using backgrounds that came from elsewhere. That means that they wanted to make their own music. And some found a way with their computers, sequencers, etc. to move forward to produce themselves. After that, how could I say it… they weren’t able to integrate… in fact it was Orishas who were the first to try and who were able to mix the beat of rap with Cuban music, I don’t know, like with son for example, the rumba and all those things. I think that they opened a new path.

In this way, Hernandez describes the musical evolution of rap as a continuum starting out as a mimetic approach toward American production and, little by little, developing its autonomy by drawing from national musical production. Referring to Orishas, she insisted on the necessity of intertwining their musical production with elements of Cuban popular music.

If we look closely at the case of the Orishas group, three of its members formerly belonged to Amenaza, one of the pioneer rap groups in Havana. They signed a contract with a record company based in France and reorganized themselves under the leadership of a producer who put them in contact with a young sonero8. Their first album A lo cubano became a huge success in 1999, coinciding with the craze for the old soneros of the Buena Vista Social Club. The record included in its orchestrations elements of son, particularly in the song 537 Cuba, which drew heavily on the hit song Chan Chan by Compay Segundo. Studying this model more closely makes one wonder about the process of “cubanisation” promoted by the ACR. Does it mean using orchestrations such as those of the Buena Vista Social Club employed by Orishas [Audio Extract 1]? Perhaps. At any rate, one cannot deny the revival of son in recent years. Paradoxically, while the interest for son has been declining considerably in the last decades, particularly amongst Cuban youth, this musical genre has become very attractive in the international market (a crucial point I will consider more thoroughly later in the text), favouring its revalorization and heritagization as Cuba’s national musical tradition.

Within the ACR, the staff were keen to promote a policy of musical fusion, encouraging groups to work with musicians.

GH [Grisel Hernandez]: We want to make records that aren’t home-made, like the demo that they [the rappers] did. We want quality records…

B [Bastien]: And how do you obtain this quality?

GH: They must become professionals, they must have musicians. So these projects take time. This is further complicated by the fact that they produce the music with their machines, and because they aren’t musicians themselves, they don’t understand how to incorporate musicians.

In this extract, we can see that state rap promoters stress the importance of the musical qualities of rap projects without considering the rappers to be musicians. It is only when rappers collaborate with legitimate actors of the musical field that their work is thought to reach proper quality standards. This gives us an important indication of how music is considered in Cuba. Indeed, the perception and assessment of music tends to be of a very academic kind. Accordingly, a musician is someone who has been trained in a musical school for at least six years, making it hard for someone who does not fit into this category to explore other ways of being a musician. This leaves little space for a more performative understanding of music, one that does not rely on the evaluation of people’s educational curricula as musicians.

The interviews I carried out with people in charge of the two major institutions that promote rap in Havana illustrate the tensions surrounding the criteria of legitimacy of this form of expression in the country. While Landroe Torres of the AHS values rap as a speech that brings about constructive criticism of society, Hernandez of the ACR emphasizes its musical qualities and more particularly the salience of certain soundings deriving from the national musical production (its ability to “integrate” and “mix” with “Cuban music” proper). Torres's perception of reggaeton almost as a virus, contaminating rap with its inferior quality, implies a completely different approach of her institution to that of the ACR, where the majority of groups perform reggaeton. This disjuncture between the AHS and the ACR illustrates a dualism in the politics of rap promotion and a duplicity in the discourses seeking to legitimize this genre. The setting up of the ACR has, in fact, contributed to a division among the rappers themselves by enabling the professionalisation of a few at the expense of all the others. This division is accentuated by the ACR’s controversial policy of musical promotion that advocates a forced fusion between rap and popular music as the sole guarantee of the legitimacy of Cuban rap.

Following these developments, a split took place among the rappers. Whereas before, the Havana rap scene was considered underground as a whole, a small group of rappers started claiming exclusive paternity of the label "underground", reducing the scale of its application, and rejecting all the others as “commercial”. With this move, what they saw as a process of commercialization in Havana rap scene became the object of their criticism. Crucial for my argument on the importance of musical considerations when examining the Cuban rap scene, is that in this case the discrimination between “underground” and “commercial” relied chiefly on issues of sound elaboration. Thus, the musical dimension became the focus of attention, the key ground of a contention that could legitimize competing claims. Accordingly, "underground" for these Cuban rappers came to refer to the following US sound aesthetics, and to be opposed to a "commercial" counterpart that encouraged the incorporation of local musical influences.

What we have here are two sources of authenticity - the “original” US sound aesthetic, and proper “Cuban music” - both tied to musical production, supporting two clashing views of rap. This, we may provocatively argue, is where the rappers “backgrounds” take the front of the scene. To delve deeper into these issues, I now turn to the process of musical production itself. Challenging interpretations that reproduce a non-musical idea of rap, I will pay attention to the representations of the members of a group of rappers who consider themselves to be “underground”. I examine how they think about and construct a sound for their rap, defining their own criteria of legitimacy and thus opposing the policies of institutionalized promotion.

The musical production of an “underground” collective

In Havana, rappers define their practice by referring, to a large extent, to the Anglo-Saxon terminology. They present themselves as "MC's" who declaim lyrics (lyricas) on top of a musical background that they literally call “background”. Those who compose these backgrounds are called producers (productores). The backgrounds that make up the musical framework of rap are essentially composed of a strong rhythm section, and often also of a melodic part.

The heavy and predominant rhythm section called the“beat”is characteristic of rap. It is composed of a strong base line, with different percussions that correspond generally to the basic components of a classical drum section, such as the bass drum that produces the lowest sound, the snare drum that produces a higher pitched and metallic sound, and finally the Charleston whose sound comes from the clash between two cymbals. In the case of the bass, as with the percussions, the sounds used can come from musical instruments typical of the jazz / rock repertory (double bass, guitar, bass guitar, keyboard, drums, percussion of all sorts), from synthesized sounds elaborated with a computer, or from pre-recorded extracts drawn from existing musical pieces (like their US counterparts, Cuban rappers refer to these extracts as “samples”). Finally, the melody line can come from a wide variety of melodic instruments (guitar, piano, violin etc.), from synthesized sounds, or from samples.

The sound arrangement that makes up the musical architecture of rap can vary from that of a rhythm section, in which rhythmic patterns are repeated, to a musical formation of several instruments in which the rhythm section features prominently. Sound arrangement can result from a performance of “live” musicians or from recordings over which the MCs rap. All the rap groups I encountered in Havana used pre-recorded backgrounds taken from CD’s, on which they rapped.

The collective on which I focus my attention here was called L3 y 89, and comprised about ten male members. Three of them were particularly involved in music production activities. These men were between 20 and 25 years old. Socio-economically, none of them came from very poor families, and all could be said to be part of Havana’s middle class. While no one had studied at university, the majority had received manual or technical training. "Racially" speaking, these young men were officially classified either as "blacks" or "mulattos". Although in its first stages, members of the rap scene emphasized their identification as "black", the majority of the rappers I studied in 2005 were less concerned with this racial identification. In saying that, I do not intend to minimize the racial dimension of what I have called the construction of a "collective identity" among the rappers (Birchler 2008). Nevertheless, compared to an earlier period where preoccupation with racial issues was very central to the development of rap, racial identification turned out to be less significant in 2005. Tellingly, the rappers’ concern to denounce racial injustice had been partly replaced by the denunciation of economic injustice.

During my fieldwork, almost all the members of the Havana rap scene were Cubans from Havana city (this is a major difference with the multi-cultural setting of rap in New York City and the subsequent diasporic nature of this expression). I say almost because two of the rappers who collaborated with L3 y 8, called Inti and Maguesh, were from Aruba and Mozambique respectively, and were in Cuba for purpose of study. In spite of the scarce presence of foreign rappers, the Cuban people I met relied on the support of transnational actors to help them develop their musical activities10. This is exemplified by the case of Randi, which I now consider in more detail.

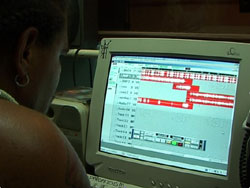

On several occasions, I was able to observe Randi, the musical producer of L 3 Y 8, work as he created his “backgrounds” (Figure 1). He spent long hours in front of his laptop, a relatively new model that his friend Maguesh, (the Mozambican participating in the L 3 y 8 project) had given to him. In order to produce these backgrounds, Randy relied exclusively on digital technology. The growing number of possibilities for computers to process digital data, be it music or even video, has enabled people with no more than a computer and a microphone to have a “home studio” technology that allows them to produce music and to record as many instruments and voices as they wish. Randi, who studied computer sciences, was skilled in using these resources. Computers are rare and expensive commodities in Cuba, and any young person who owns one is likely to raise suspicion. Most of the rappers I knew did not own one directly, and those who had one had usually obtained it through contacts with foreigners. The software for processing sound used in musical composition were on the contrary widely shared and more easily available.

Partly at least, this technological scenario may contrast with a street image of rap, and is a recent development in the Cuban scene. Indeed, whereas the first stage of rap development on the island was characterized by relatively spontaneous expressions, street practices and very little or no technology, the rappers I observed in 2005 were highly committed, if not dependent, on a strict interpretation of how rap production should be achieved. In fact, I got to know very few examples of groups producing their music by other means than those employed by Randi - a noticeable exception being the "omni" collective, from Alamar (East of Havana), some of whose members made backgrounds with an old Remington style writing machine.

Figure 1: Randi creating backgrounds with digital technology.

Randi created his backgrounds mostly by“sampling”. Sampling consists of extracting a part of a piece of music - a sample - from an existing one. The sample can be a sound that is isolated and modified. For instance, one can modulate its length or its pitch. It can also be a loop, in which a small musical pattern is taken out of its original context and inserted in a new one. Sampling is one of the characteristic techniques of rap. Through sampling, rap quotes, re-incorporates and reformulates a pattern made up of extracts, thus building a new meaning from a group of musical signs that have been extracted and put together again (Art press 2000: 7).

Randi's work was unanimously praised among the rappers - he has been successful in constructing his own sound drawing on an existing repertory. He delved into his record collection to find the basic material with which he composed his original musical pieces. Although the supply of foreign music was limited in Cuba, rap albums were frequently exchanged between rappers and they could easily be copied. Randi took the majority of the sounds he used from US rap and to a lesser extent from Canadian or French. These records made up the majority of his collection. But his collection also contained several records of Tchaikovsky, for whom he had great admiration. Randi, who enjoyed loud sounds and pompous harmonies, explained to me that he often borrowed from Tchaikovsky for his samples [Audio Extract 2]. While Cuban youth rarely listen to classical European music, it appears that Randi became a connoisseur and a fan of Tchaikovsky via rap.

Reference to Cuban musical tradition in his production was generally limited to isolated percussion sounds such as the Bata drums [Audio Extract 3]. Once integrated into his arrangement, they go relatively un-noticed. The musical framework he elaborated was sombre and often dark. Symbolically, the sound evokes weightiness, heaviness and sadness. The strong repetitive beat hammers the tempo; the bass of the rhythmic section makes the skin quiver. Overall, this musical register sounds radically different from most Cuban popular musical production [Audio Extract 4].

When discussing these issues, the rappers of L 3 y 8 were very dismissive of other rappers who made fusions with other musical styles. Referring to Cubanos en la red and Tellmarys, two artists from the capital who had developed a style of rap incorporating many other influences, Randi said, “they don’t even know themselves what they are doing anymore, they are completely lost”. In the introduction track of L 3 y 8’s album, Randi, portraying himself as a purist, puts forth a program that “mixes rap with rap, something few groups do”. By saying that, Randi criticizes the artists that mix rap with other musical influences, considering it something that can only corrupt it. Accordingly, the underground musical production has to stand by the underground project. Just as the texts must provoke and disturb the audience, the sound must agitate them as well.

In this respect, it is significant that in Cuba, such underground rappers generally consider their production to be a "protest music"(música de protesta). Describing their music to me they called it a strong or hard sound(sonido fuerte). Papá Humbertico, a rapper and underground musical producer close to Randi explained: “I don’t want it to sound like salsa, soft. I want it to sound harsh. If it isn’t harsh, it won’t touch people, it doesn’t reach them. When you listen, your heart has to beat “boom boom”!". Thus, we can argue that the aesthetical sonority these underground rappers strive for is in stark contrast with the seduction that characterizes the vast majority of the popular music promoted in Cuba. In this respect, we understand better the apparent contradiction of Randi condemning the recourse to external musical influences while at the same time doing so himself with the incorporation of influences like Tchaikovsky. What he was actually attacking was not the fact of mixing influences - which is at the very base of rap production - but rather the fact of mixing rap with local dominant influences (Cuba’s most popular dance oriented styles), which would have implied, according to him, a kind of compromise. We are dealing here with a confrontation on the grounds of aesthetic as they are connected to social life. Randi's goal, through his musical production, is to put forward an aesthetic of disenchantment that confronts the enchanted, hedonistic aesthetics of Cuba’s popular dance music [Audio Extract 5].

Another strategy L 3 y 8 would use to further differentiate themselves, radically, from popular music was to claim their practice as being more than “musical”, as being “cultural”, as belonging to the hip-hop culture grounded in American aesthetic and characterized by a critical discourse on society. We must recall the expert-driven conception of music discussed earlier to understand the sometimes derogatory image rappers had of their own musical production, as shown in the following extract of interview with rapper Papá Humbertico :

B: Is rap a style of music for you?

P.H: Yes it’s clear that it’s a style of music, yet…

B: Do you consider yourself to be a musician?

P.H: Me, a musician? No

B: Then what?

P.H: Like a poet

B: So you are closer to poetry than to music?

P.H: Yes, yes

B: But you also do production, backgrounds, don’t you?

P.H: True

B: So you also make music?!

P.H: Yes, but I never studied music and I don’t have any musical knowledge.

P.H: Yes, ok. But me, as I see things, how should I say it… as it comes to me, I do a background and I see if it sounds good like that, that it sounds cool and then, I leave it like that [I stop there] Perhaps if I give a background to a musician, he would say “what’s this, what kind of shit is this?” You see? But as a rapper, that is fucking great.

In this extract one can really see how difficult it is for the rapper producer to consider himself a musician, given that he has not attended a legitimate music institution. Papá Humbertico's last comment illustrates the musical depreciation of his own production, when he imagines a legitimate expert criticizing it as worthless. Yet at the end, he matches this with his own rapper’s point of view, which values his musical endeavour. The rapper claims authority in an area where academic musical criteria alone do not suffice to evaluate rap. The allegiance shown by these underground rappers to the “original” musical codes of rap13 is geared at claiming independence via the sound and putting up a barrier between themselves and most of the music promoted in Cuban media.

The desire to break away from the sort of Cuban popular music that benefits from more promotion in the Cuban public sphere is often misunderstood by musical commentators. In her 2006 article on the transformations of rap in Cuban popular music, Grisel Hernandez of the ACR detailed some of the tendencies found in the musical production of rap. She notices the inclination of those who do not want to make their music sound Cuban, and who are closer to US aesthetics. Arguing that this is due to a lack of material means, Hernandez classifies these groups at the bottom of the ladder in the evolution of Cuban rap (Hernandez 2006: 4). In doing this, she denies underground producers the possibility of making a deliberate strategic aesthetic choice. While their relationship to the local cultural context is expressed more clearly in their texts than in their music, the rappers I engaged with categorically refute the argument that their production lacks somehow in “cubanity”. As Papá Humbertico said “Forget about how it sounds! If you do it in Cuba, if you’re Cuban, where else could it come from? If you were born here and it was made by a Cuban?” Pushing his reflection even further, this rapper wondered why the question of “cubanity” is never raised in regards to ballet or flamenco. “Why don’t they dance ballet with the salsa? I don’t know”.

By claiming another frame of reference - one that relies on different aesthetics - the rappers diverge from the usual criteria of judging musical production and assert alternative sources of legitimacy. Given that both musicians and scholars usually fail to recognize rap as a fully-fledged musical genre in its own right, and that even rappers distance themselves from the more orthodox musical field, one may still wonder about the relevance of approaching rap from a musical perspective. But here is where an additional line of interpretation may be fruitfully pursued. To reassert the importance that the musical dimension of rap may acquire, and to strengthen my case about the scholarly attention it deserves, other considerations can indeed be made on the roles and the relationships between speech and musical production.

In the case of timba, Perna shows that performers tend to reject deep meanings, based on mainstream moral standards and instead praise hedonism. On the contrary, by using political speech’s codes, we may consider that rappers with their texts tend to stick to what Perna calls the "rationality of the dominant discourse" (Perna 2005). To consider rap solely as a form of political speech, however, can also provide commentators venues to discredit it and highlight its inconsistencies. Indeed, far from resulting always in an acknowledgment of its quality, such an approach of rap may also be seen as a way of confining it into the realm of the political speech, a dominant14 discursive rationality whose codes the rappers may not handle properly, and on whose grounds their credibility may be limited. For rappers, as insightful their observations might be, are not prepared to compete on the highly codified terrain of the political speech. This is where musical production (together with other elements such as body language, clothes, lyrics, etc.) can provide a venue for escaping the frame of reference of discursive rationality, to shift the grounds of the contention, and to express disagreement vis-à-vis dominant conceptions via the aesthetics of sound. In the case of musical production, it becomes indeed harder to channel interpretations by claiming equivalences between musical and political discourse. I would argue that by denying the rappers the authority to speak as legitimate actors of the field of music, the promoters want to keep the potentially subversive charge of the musical discourse under control.

Randi explained to me one day that rap was music “to listen to, not to dance to”. He made a clear distinction between the two categories of music: one to reflect with (musica para escuchar, reflexionar) and one to dance, which according to him suggests that life is a never-ending party. “Todo no es como lo pintan, al contrario” (everything isn’t like it is portrayed, on the contrary), he commented to me on several occasions, thus expressing the idea that the marketed image of a joyful and happy Cuba tend to deny the harsh social reality. On a solo album that he produced, Randi included a musical interlude consisting of one minute of silence (Un minuto de silencio; Jodido protangonista; Randi Acosta). We may argue that such silence time for reflection is at the antithesis of the heavy orchestration found in much Cuban popular music.

Several studies have dealt with rap as a global phenomenon, questioning the process of its adaptation to different contexts. I would argue, together with Baker that it is rather its “non-adaptation” that is significant in the case of the Cuban underground rappers (Baker 2006: 242). The lack of inclination towards typically Cuban sonorities, the use of European classical music and an allegiance to the original US reference (where the majority of the codes of this production were elaborated) clearly show opposition to the process of musical fusion that is presented by the authorities as the guarantee of the authenticity of Cuban rap.

Challenging “cubanity”

After having looked at the historical articulation between music and representations of national identity in the first section of this article, in order to illuminate further what is at stake in the question of “cubanity” and outline some of its contemporary trends, it is important to consider the place music has occupied in this Caribbean island during these last decades of crisis. This will enable me to delve deeper into another set of forces, related to market driven agendas, which play a crucial role in shaping national cultural identity.

In order to tackle the issue of Cuban identity, I must begin by emphasizing that Cuba is still relatively isolated from Western countries. In addition to the continuing US embargo that asphyxiates the country, the government pursues a policy of deliberate cultural isolationism towards the West in order to starve off any form of “capitalist contagion”. For the last 50 years there has been very little migration to/from the country. Furthermore, media such as internet or television are subject to strict regulation. In addition, the type of political regime that has been in power since the Revolution of 1959 is characterized by an exacerbated form of nationalism that is reinforced by continual attacks on the part of the US government. The national referent is glorified as a model of resistance and heroic struggle against the domination of the most powerful economic and military country in the world, the USA. “Patria o muerte” (homeland or death), the national motto, leaves few alternatives to a patriotism that is tightly intertwined with the revolutionary referent. All these factors combined contribute to highlight national identity as the paramount frame of identification.

In spite of the government’s ideologically selective isolationist policy, the “special period” can be characterized by an opening up of the country, and saw Cuba having to rely increasingly on external exchanges with the Western world (especially through trade relations and the development of tourism) in order to compensate for the most dramatic effects of the crisis. This relative openness has brought about side effects that have escaped the control of the authorities, prompting scholars to recognize the existence of “independent cultural circuits, clandestine and parallel to the controlled official culture" (Exner 2004: 71). Thus, Cuban people have increasingly access to transnational cultural flows promoting alternative models to those proposed by the state. Rap belongs to this type of model whose codes have been developed abroad. By adopting them, rappers claim a more inclusive form of “cubanity”, one that is eager to integrate cultural referents from abroad and that contests the version of “cubanity” conveyed by official policies of musical promotion.

Once we agree that national identity is a construct under constant negotiation, the Cuban case suggests that periods of crisis may become pivotal moments bringing to the surface challenges and call for an updating of the norms and values that serve as referents in the discourses and practices of citizens. This process of identity updating brings about negotiations through which models of "cubanity" are contested and transformed. Within this process, the state - via its public policies - plays an important role in providing and channeling identifications. It holds the monopoly of symbolic violence (Bourdieu 1972: 18) to the extent that it has important resources, both material and symbolic, that enable it to name, categorize and identify (Brubaker 2004: 76). By subsuming and trying to incorporate under an overarching umbrella what they considered as "underground", the state promoters tended to impose their criteria of “cubanity” on rappers. Indeed, they were asserting a sort of state "underground" which was favourably converging with the characteristics of Cuban socio political organization.

Furthermore, the musical criteria on which these promoters relied are emblematic of a contemporary orientation in Cuban musical promotion policies. Since the dramatic crisis of the “special period”, music has been increasingly considered a marketable cultural resource, a commodity. Given the global craze for Cuban music - as confirmed by the international success of Buena Vista Social Club - it has become a leading export product. The strategic importance of music has become all the more obvious in the context of the current crisis, as people struggled to get by with meagre resources. The companies that hire professional musicians are profitable for the state and are increasingly concerned with profitability. Music has become a key economic sector. Consequently, as stated by Pacini Hernandez, musical production in Cuba tends to play more and more to the tastes of potential consumers.

Cuban musicians no longer have the luxury of developing their music according to local aesthetic conventions, without paying attention to marketability. Their music now has to sell. And, to sell, it has to satisfy the expectations and aesthetic preferences of non Cuban consumers who are not only geographically but also culturally far removed from the musicians and their local communities (Pacini Hernandez 1998: 120)

As mentioned above, the policies for the promotion of rap have a double aspect. Rap is officially praised as a revolutionary form of expression. However, with regards to its promotion, the accent is put on its capacity to gain commercial success, thus playing up to the stereotypes of what international audiences consider being Cuban.

This duplicity in discourse is characteristic of a phenomenon that Cubans refer to as the “double standard” (doble moral). This means that two systems of value, two moral referents co-exist in one’s daily life. On the one hand, there is the standard attuned to the principles defended by the revolution. On the other, there are the necessary strategies and practices people develop in order to get by in the difficult socio-economic conditions of present day Cuba. In my previous work, I stressed the important role that criticism of this "doble moral" occupies in underground rappers' texts (Birchler 2008).

The construction and defence of the musical posture I examined in this article belongs to this same strategy of criticism. The group of self-ascribed "underground" rappers I considered rejected the musical agendas imposed by the state rap promoters by putting forward a new “underground-ness”, differing from the "all inclusive" state sponsored one. This made them very reluctant towards any kind of musical fusion. Such stance appears stronger from a symbolic point of view in a country where "mestizaje" is considered to be one of the foundations of national identity. The compelling answer of Papá Humbertico – "If you do it in Cuba, if you’re Cuban, where else could it come from?" – deserves to be recalled here, as it exemplifies the rappers’ claim to perform a Cuban musical practice without denying its foreign origin. In this sense, we may argue that these rappers are de facto involved in a process of "mestizaje", but one which is in radical opposition to the process of fusion that is so fashionable in the music industry, and that according to them follows a superficial logic of short-term success.

Conclusion

A frequent bias in the analysis of rap has often led scholars to forget that this phenomenon is strongly rooted in the musical field. As Hennion (2005) points out, most commentators do not apprehend rap as much more than a politically grounded speech. This reflects a significant level of prejudice towards what many still see as a non-musical object. From its beginnings, the musical qualities of this genre have been persistently denied and overlooked. Such a reductive stance deprives the analysts of fundamental insights into a crucial layer that is integrally constitutive of this phenomenon. Indeed, the strategy of musical composition in rap is a site of meaning production whose analysis can offer complementary insights to other aspects such as the performance's conditions or the texts.

These were precisely the insights that this paper wished to capture by considering the case of rap in Cuba - a country in which music has acquired a central place for imagining the nation. The investigation of the recently emerged phenomenon of rap in Cuba enabled me to shed light on local policies’ endeavours to integrate and co-opt a new musical expression in a time of crisis and increasingly global economic integration. Such endeavours required the authorities to define their posture toward a new musical trend while formulating at the same time the key features of the context of reception, i.e. the Cuban cultural referent.

The article has highlighted the conflicting perspectives of a group of young rappers and the institutional agents in charge of the promotion of rap music. Focusing on musical production, I tracked the controversy regarding a supposed lack of "cubanity" in rap’s sound. Such critique of a deficient "cubanity" affected rappers striving to maintain an "underground" posture. As explained when discussing the rappers’ strategies of musical production, this posture made a point in perpetrating distance from Cuban popular music, a genre that benefited from the most concerted promotion efforts in the island. In their endeavour to “Cubanize” rap music, cultural promoters outlined a doctrine of musical fusion between rap and other genres of Cuban popular music. Distancing themselves from such views, the rappers criticized any attempt to promote stereotyped representations of Cuban reality through music. Crucially, their critical and embittered analysis of Cuban society was delivered not only through their texts, but also via what I called a disenchanted sound aesthetic.

Whereas for those rappers the question of the "cubanity" of their expression seemed to matter little and was quickly resolved, it was its "underground-ness" that preoccupied them. Bypassing the Cuban/non-Cuban binary on which the institutional agents relied to assess the validity of musical production, the "underground" rappers claimed the respect of another frontier they themselves erected and strenuously maintained with “commercial” rap production, which they stigmatized and denied of any legitimacy. This shift in conceptualising the debate is very significant. It may be seen as empowering the rappers, who by decentring the terms of the contention, are moving away from an identity focused perspective (that of “cubanity”), towards a concern for socio economic critique (the opposition to the "commercial").

Two significant elements of reflection and critique can be drawn from this relational confrontation. First, by opposing what they perceive as a pervasive market-driven orientation within cultural promotion politics - a key aspect of the “underground” being the opposition to the "commercial" - the self ascribed underground rappers denouncethe existence of a double standard. The evolution in policies of rap promotion in Havana reflects tensions that are running through a society that has partially opened up to the market economy while still maintaining a hostile anti-capitalist discourse. Thus, musical production emerges as the response of a group of young actors emphasizing the growing gap between the fundamental principles on which Cuban society has been built since the Revolution, and pragmatic policies that appear to them to be driven by the lure of short-term profits. Second, by dissociating themselves from other trends within the Cuban rap scene, the “underground” rappers help us recognize the diversity and plurality of the scene itself. In contrast with the overarching unity presupposed and advocated by the state promoters, the rap scene seems indeed to be a catalyst for different - sometimes even contrary - trends to emerge and find expression.

By maintaining a harsh sound that embodies their refusal of the official doctrine of fusion, the rappers challenge stereotyped representations of “cubanity” and outline an alternative societal model. They affirm their right to be different, to perpetrate a genre of Cuban music without it having to be danceable, exuberant and joyful – as international demand seems increasingly keen to expect. Through their musical production, the rappers are thus questioning and struggling against any supposedly stable and unified Cuban identity. Claiming the right to create and shape spaces for a diversity of creative expressions within Cuban society, the rappers oppose what they perceive as the state’s willingness to oversee all artistic endeavours in the island. This is a strong stance directly challenging an egalitarian but also homogenizing conception of national identity that threatens to leave little space for any radical expression of alterity.

Acknowledgements

I would like to first express my gratitude to the rappers, promoters and all the persons who are at the core of this study for their time and availability. I am also very grateful to Valerio Simoni, Simone Abram and the anonymous reviewers for the useful comments provided.

References

Acosta, Leonardo. 1987. From the drum to the synthesizer, La Habana: Jose Marti Publishing.

Art Press. 2000. Territoires du Hip-hop. Paris. [2000]

Baker, G. 2005. !Hip Hop, revolución! : nationalizing rap in Cuba. Ethnomusicology: Journal of the society for Ethnomusicology. 49(3).368-402.

- - - 2006. ‘La Habana que no conoces’: Cuban rap and the social construction of urban space. Ethnomusicology Forum .15, (2). 215-46.

Basso Ortiz, A. 2001. Rap: Por el amor al arte? El Caiman Barbudo n°303. http://www.caimanbarbudo.cu/caiman303/page/rap.htm

Birchler, B. 2008. Farandula no! esto es asunto serio; La construction d'une identité collective au travers de la pratique du rap underground à la Havane. Master thesis, University of Neuchâtel.

Bourdieu, P.1972.- Esquisse d'une théorie de la pratique. (Paris), Editions Droz.

Brubaker, R. 2004. Au delà de l'identité. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales.- http://www.polychromes.fr/IMG/doc/Brubaker_au-dela_de_l_identite.doc

Cachin, O. 2001 [1996]. L'offensive rap. Paris: Gallimard Découvertes.

Casanellas, L & HERNANDEZ, G. 2001. Hora de abrir los ojos… ¡el rap cubano existe!. Salsa Cubana año 5, (16) 2001.

Castro Medel, O. 2005. ¿Prohibido el reguetón?". Juventud Rebelde (La habana).

De La Fuente, A. 2005. Cuba's racial democracy: What now ? 16 p.-http://www.newschool.edu/GF/centers/janey/conf05_De-la-Fuente.pdf

Exner, I. 2004. Poderes y paradojas en una (sub-)cultura emergente. Observaciones acerca del movimiento de hip hop en La Habana. Revista iberoamericana.4 (14). 69-89

Fernandez Diaz, A. 2000. ¿Poesía Urbana? o la Nueva Trova de los Noventa. El Caimán Barbudo 296. 4- 14.

- - - 2002. Los futuros immediatos del rap Cubano".- juventud rebelde 13 nov 2002

Froelicher, P. 2005. "“Somos Cubanos!“– timba cubana and the construction of national identity Cuban popular music".- Revista Transcultural de MúsicaTranscultural Music Review.- 9.- http://www.sibetrans.com/trans/articulo/167/somos-cubanos-timba-cubana-and-the-construction-of-national-identity-in-cuban-popular-music

Habel, J. 2009. Cuba, en quête d'un modèle socialiste renouvelé. Le monde diplomatique. janvier 2009. 14-15.

Hennion, A. 2005. Musiques, présentez-vous ! Une comparaison entre le rap et la techno. French cultural studies 16(2).121-34.

Hernandez, G. 2006. Avatares del rap en la música popular cubana. conférence donnée à la Casa de America le 24 juin 2006.-http://www.hist.puc.cl/iaspm/lahabana/articulosPDF/GrizelHernandez.pdf

Manuel, Peter. 1987. “Marxism, nationalism and popular music in revolutionary Cuba”. In: Popular Music 6 (2).161-78.

Moore, Robin. 1994. Representations of Afrocuban expressive culture in the writings of Fernando Ortiz.“ Latin American Music Review 15 (1), .32-54.

--- 2002 “Salsa and socialism: dance music in Cuba, 1959-99.“ (ed.) Waxer, Lise Situating Salsa: global markets and local meaning in Latin popular music.New York & London: Routledge.51-74.

Pacini Hernandez.1998. Dancing with the Enemy: Cuban Popular Music, Race, Authenticity, and the World-Music Landscape. Latin American Perspectives. 100(25). 110–25.

Pecqueux, A. 2003. La politique incarnée du rap. Socio-anthropologie de la communication et de l'appropriation chansonnières. Ph.D. thesis, EHESS.Paris.

- - - 2005. Un témoignage adressé : parole du rap et parole collective. C@hiers de psychologie politique. n°7 .-http://a.dorna.free.fr/CadresIntro.htm.-

Perna, V. 2005. Making meaning by default. Timba and the challenges of escapist music Revista Transcultural de Música Transcultural Music Review, 9.

Perry, M. 2004. Los raperos : Rap, race, and social transformation in contemporary Cuba. Ph.D. thesis, Austin University.

Robbins, J.1989. Practical and Abstract Taxonomy in Cuban Music. Ethnomusicology 33, (3).

Roy, M. 2001. Musiques cubaines. Arles : Cité de la musique/Actes Sud.

West-duran. 2004. Rap’s Diasporic Dialogues: Cuba’s Redefinition of Blackness. Journal of Popular Music Studies 16(1)1: 4-38.

Musical extracts

Extract 1: Orishas; A lo Cubano (A lo cubano)

Extract 2: Randi Acosta; Victima (Jodido Protagonista)

Extract 3: Randi Acosta; interludio (Jodido Protagonista)

Extract 4: Los Aldeanos; Enemigo del presente (Poesia esposada)

Extract 5: Papa Humertico; Los mismos temas (Pluma y microfono)

Author information

Bastien Birchler holds an MA in Anthropology form the University of Neuchâtel. He has been repeatedly to Cuba and conducted eight months of fieldwork in Havana in 2005 for his dissertation on underground rap and collective identity constructions. He currently works as independent filmmaker in Geneva.

Endnotes

1 Timba is a contemporary form of Cuban Salsa.2 As Pecqueux has shown, there is an ambiguity in this representation as the rappers self-assert their representativeness without it having been ratified by the people they pretend to represent.

3 This claim of "talking real" is rooted in a dialectical relationship opposing reality (truth claimed by the rappers) on the one hand and ambient lie on the other hand. 4 This political statement in the Cuban case had a clear strategic dimension given the fact that to fight the colonial Spanish power, the elite had to build an alliance with the black and mulattos who represented a large percentage of the population. 5 Reggaeton is a musical genre that recently expanded in Cuba, most noticeably since 2004 in Havana. This genre is close to rap music (most of the first reggaetoneros, in Cuba and abroad, were previously rappers), incorporates Jamaican influences (raggamuffin) and some latin music patterns. It is said to have emerged between Puerto Rico, Panama and the USA (Castro Medel: 2005). Reggaeton is usually viewed as more melodious and much more dance oriented. Generally speaking, reggaeton is perceived as party music, much less concerned with social issues than rap. 6In his article, "Practical and Abstract Taxonomy in Cuban Music", James Robbins (1989) defines empresas musicales as cultural institutions, "individually budgeted organizations whose function resembles a cross between a musicians' union and a talent agency. Empresas are responsible for correlating musical services, pay scales, work quotas, and musicians' rating" (Robbins 1989: 381). 7 Backgrounds is the name employed by rappers to describe the musical compositions they are rapping over. 8 A sonero is a musician who plays son music. Son, a genre rooted in rural folk music (musica campesina), is widely considered to epitomize traditional Cuban music, integrating elements of Hispanic musical tradition as well as African ones.9 This name is a reference to the 3rd and 8th letter of the alphabet. The letters "C" and "H" correspond to "Culture" and "Hip-hop".

10 Indeed, a number of more or less organised actors provided support for the rap scene. Black August, a grassroots organisation, was among the main US based groups to support Cuban rappers, raising funds for US artists to perform at the Habana Hip-hop festival and helping facilitate travels abroad for some Cuban rappers.12 Benny Moré is one of the most celebrated artists of Cuban music history. He is known as a true self-taught musician.

13 Of course these codes are interpreted as such. The fact that "original Rap music" is the result of numerous incorporations is, in the rapper's discourse, usually silenced.

14 Political speech is highly considered and benefits from a privileged status in Cuba. With Fidel Castro as a brilliant model regarding the art of rhetoric, Cuban people have been trained to acknowledge the political speech’s power. At the time of my fieldwork for instance, every time Fidel Castro was giving one of his speeches, his voice would dominate the media arena, leading to the interruption of other TV programs.